Well? Are chemicals killing us? That’s the title of study concerning news media coverage of chemical risks, and it concludes that the media over-reacts to chemical risks.

According to the press release: “Majorities of toxicologists rate most government agencies as accurately portraying chemical risks, but they rate leading environmental activist groups as overstating risks, according to the survey by George Mason University researchers.”

The study also says that industry gets it right most of the time. And, the study says that Wikipedia is more accurate than the New York Times on issues of risk analysis and communication.

The study was performed by the Center for Health and Risk Communication at George Mason University.

So how was this study done, and why did it reach such negative conclusions about the media?

Just as scientists need to be skeptical of overly broad and politically loaded claims in science, we also need to be skeptical of similar claims in social science.

“Toxicologists Opinions on Chemical Risk” said:

- • Toxicologists give the regulatory system a vote of confidence, even though 40 percent think EPA overstates risk;

- • Only one of four believe the US regulatory system is inferior to that of Europe, where the precautionary principle has the force of law;

- • Most fault (government) regulators and the media for not doing a good job explaining chemical risk to the general public.

- • 95% of toxicologists surveyed believe that Greenpeace is overstating risks, with similarly high ratings for PETA, the Environmental Defence Fund and other environmental groups, while, at the same time, around 60 percent have faith in PhRMA and the American Chemistry Council;

- • News publications overstate risk according to 90 percent of toxicologists, while broadcasters are nearly universally overstating risk;

- • 56% “describe as accurate the portrayals of risk” by Wikipedia and WebMD,

- • 3% describe local TV news as accurate

So, does the media get science wrong 85% to 97% of the time? No, that’s not what the study is saying. The study actually says that in the opinion of a select group of toxicologists, this kind of environmental or media or government institution tends overall (on a scale of 1 to 5) to be either more or less accurate.

Strictly speaking, this is not an “accuracy study.” Accuracy studies in communication research involve a specific method designed to take samples of real articles and ask respondents to rate the accuracy of specific statements based on multiple questions.

This study asks respondents to rate an overall impression of accuracy, but not any specific instances of inaccuracy. The method results in numbers that seem to lead strongly in one direction but, in fact, have little serious meaning.

There is also an issue with the sample universe. Does the Society of Toxicology represent ALL toxicologists, or even a representative sample of toxicologists? Actually, no. These are the conservative toxicologists. There is also a very different organization called the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC). They are far less industry oriented.

And finally, how are the questions asked? The report says that 3 of 4 toxicologists reject the “precautionary principle.” But (and we can only assume that this reflects the survey instrument) the definition of the precautionary principle in the study is that it “mandates that a substance suspected to cause harm should be banned even in the absence of scientific consensus.”

However, the precautionary principle, defined by Raffensperger & Tickner (found in Wikipedia), “is a moral and political principle which states that if an action or policy might cause severe or irreversible harm to the public or to the environment, in the absence of a scientific consensus that harm would not ensue, the burden of proof falls on those who would advocate taking the action.The principle implies that there is a responsibility to intervene and protect the public from exposure to harm where scientific investigation discovers a plausible risk in the course of having screened for other suspected causes.”

According to Von Moltke: The Bergen Declaration defined the Precautionary Principle as, “Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation.” http://www.ec.gc.ca/seminar/VM_e.html

So, has the study defined the principle correctly? Its not that regulation is mandatory in the absence of scientific consensus. Its that industry has a burden of proof in cases where harm is reasonably possible.

Clearly, the George Mason group has not provided an accurate statement of the precautionary principle. Rather, they have given us an example of how a question can be phrased so as to bias a survey toward a preferred result.

And thus, can we really conclude that the study itself provides anything worthwhile? That Wikipedia is more accurate than USA Today? Or that industry toxicologists dont like the media? These are ho-hum moments at best.

But it does show that we need to be skeptical of political posturing in the guise of social science.

Environmental Action Archive

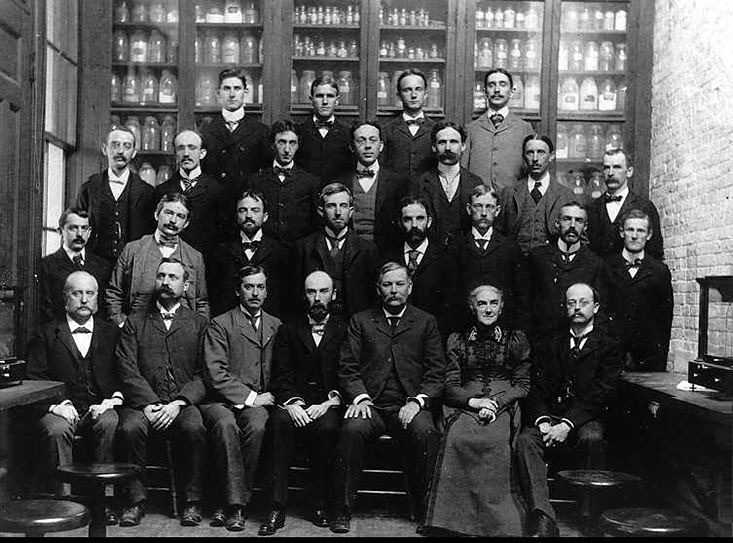

Environmental Action Archive Ellen Swallow Richards

Ellen Swallow Richards The hats that created bird sanctuaries

The hats that created bird sanctuaries  Pollution regs saved lives

Pollution regs saved lives LA's first big smog

LA's first big smog ¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The

¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The ¶ Dymaxion car

¶ Dymaxion car

¶ Aldo Leopold

¶ Aldo Leopold