Environmental concerns and conflicts have surfaced throughout human history, from the earliest settlements to the latest headlines. This comes as a surprise to many people because our emphasis in history has all too often been on war and politics, rather than environment, culture and development. Yet the evidence of longstanding concern for the environment has been readily available in manuscripts, publications and historical archives. It can be found under labels like conservation, public health, preservation of nature, smoke abatement, municipal housekeeping, occupational disease, air pollution, water pollution, home ecology, animal protection or many other topic areas.

“Environment,” “ecology” and other modern terms were developed as umbrellas to encompass a variety of related concerns, but the concerns and related conflicts are threaded through history like the underside of a tapestry — sometimes not visible, but always part of the fabric of life.

The broad lack of historical perspective about environmental history has its origins in neglect and misinformation. As a result, contemporary environmental issues often emerge in the mass media without context and then disappear with little more than symbolic resolution. Political conservatives seem not to recognize the reflection of their own values in conservation movements. Political liberals lack a sense of the traditions of social reform.

Dangerous myths emerge in the vacuum of history. For example:

• The myth Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring started all the uproar;

• The myth that environmentalism is just an hysterical reaction to science and technology;

• The myth that environmentalism is a passing fad with no serious ideas to offer;

• The myth that environmentalism is a substitute for religion.

These myths call to us like sirens, falsely assuring us that environmental concerns can be safely ignored. Nothing could be further from the truth. The modern global environmental crisis requires an understanding of history that is only recently becoming available.

Just as individuals are lost without their memories, civilization needs its collective memory in the form we call history. But history is not simply a static collection of well known facts any more than science is an unchanging description of the physical world. History doesn’t passively accumulate. It is the active work of historians, and their views may change, grow or coalesce around facts that only become available decades after events take place. New approaches to history often only appear when they are needed, as Howard Zinn once said. For instance, civil rights history didn’t emerge until the 1960s. Women’s history took off in the 1970s with the women’s movement.

The work of environmental history has hardly begun. It is now clear that long before Silent Spring was written or Greenpeace activists defied whalers’ harpoons, many thousands of civic activists tried to stop pollution, promote public health and preserve wilderness. They were Republicans as well as Democrats; Tories as well as Whigs; Conservatives as well as Liberals.

No one perspective or ideology has been uniquely suited to protecting the environment aside from an underlying sense of obligation to other people and to those who will come after us. For that reason we need to recall those who came before. Their struggles deserve to be remembered, and in pausing for remembrance, and learning from history, we may develop a more mature view of the challenges confronting us all. — Bill Kovarik

Nixon's green camouflage

Nixon's green camouflage Stewart Udall

Stewart Udall  First gasoline auto

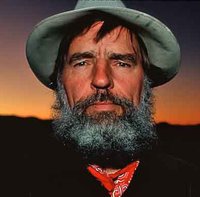

First gasoline auto Edward Abbey

Edward Abbey

Environmental Action Archive

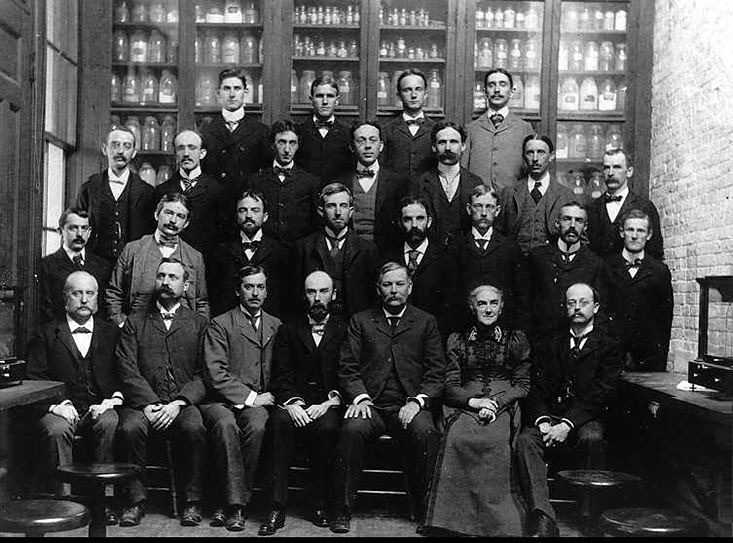

Environmental Action Archive Ellen Swallow Richards

Ellen Swallow Richards The hats that created bird sanctuaries

The hats that created bird sanctuaries  Pollution regs saved lives

Pollution regs saved lives ¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The

¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The ¶ Dymaxion car

¶ Dymaxion car  ¶ Aldo Leopold

¶ Aldo Leopold