By

Donald Trump’s election is generating much speculation about how his administration may or may not reshape the federal government. On space issues, a senior Trump advisor, former Pennsylvania Rep. Bob Walker, has called for ending NASA earth science research, including work related to climate change. Walker contends that NASA’s proper role is deep-space research and exploration, not “politically correct environmental monitoring.”

This proposal has caused deep concern for many in the climate science community, including people who work directly for NASA and others who rely heavily on NASA-produced data for their research. Elections have consequences, and it is an executive branch prerogative to set priorities and propose budgets for federal agencies. However, President-elect Trump and his team should think very carefully before they recommend canceling or defunding any of NASA’s current Earth-observing missions.

We can measure the Earth as an entire system only from space. It’s not perfect – you often need to look through clouds and the atmosphere – but there is no substitute for monitoring the planet from pole to pole over land and water. These data are vital to maintaining our economy, ensuring our safety both at home and abroad, and quite literally being an “eye in the sky” that gives us early warning of changes to come. To paraphrase Milton Friedman, there’s no free lunch. If NASA is not funded to support these missions, additional dollars will need to flow into NOAA and other agencies to fill the gap.

NASA satellite data show the spread of hemlock decline, caused by an invasive insect called the hemlock woolly adelgid, near North Carolina’s Mount Mitchell in February 2016. Brown areas have less vegetation than normal for the time of year. NASA Earth Observatory

Shared missions

The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, which created NASA, explicitly listed “the expansion of human knowledge of phenomena in the atmosphere and space” as one of the new agency’s prime objectives. Other federal agencies have overlapping missions, which is normal, since there are few neatly defined stovepipes in the real world. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is part of the Department of Commerce, works to “understand and predict changes in climate, weather, oceans, and coasts.” And the U.S. Geological Survey, a bureau of the Interior Department, is charged with “characterizing and understanding complex Earth and biological systems.”

These primary earth science agencies have a pretty clear division of labor. NOAA and USGS fund and operate a constellation of weather- and land-observing satellites, while NASA develops, prototypes and flies higher-risk, cutting-edge science missions. When these technologies have been proven, and Congress funds them, NASA transfers them to the other two agencies.

For example, in the NOAA-NASA partnership to develop the next generation of operational weather-observing satellites, NASA took the lead in prototyping and reducing risk by building the Suomi NPP satellite. That satellite, now five years old, is improving our daily weather forecasts by sending terabytes of data every day to supercomputers at NOAA. Its images also help with tasks as diverse as navigating in the Arctic through the Northwest Passage and monitoring the tragic wildfires near Gatlinburg, Tennessee. The experience NASA gained by developing the new technologies is now incorporated into NOAA’s Joint Polar Satellite System, whose first launch is scheduled for next year.

When I served as NOAA’s chief operating officer, I met regularly with my NASA counterpart to ensure that we were not duplicating efforts. Sometimes these relationships are even more complex. As oceanographer of the Navy, I worked with NOAA, NASA and the government of France to ensure joint funding and mission continuity for the JASON-3 ocean surface altimeter system. The JASON satellites measure the height of the ocean’s surface, track sea level rise and help the National Weather Service (which sits within NOAA) forecast tropical cyclones that threaten U.S. coastlines.

It is vital for these agencies to coordinate, but each plays an important individual role, and they all need funding. NOAA does not have enough resources to build and operate a number of NASA’s long-term space-based Earth observing missions. For its part, NASA focuses on new techniques and innovations, but is not funded to maintain legacy operational spacecraft while simultaneously pushing the envelope by developing new technologies.

The value of space observation

To many members of the earth science community, organizational issues between NASA and NOAA are secondary to the real problem: lack of sufficient and sustained funding. NASA and NOAA are working jointly to patch together a space-based Earth observing system, but do not receive sufficient resources to fully meet the mission.

An administration that truly wanted to improve this situation could do so by developing a comprehensive Earth observing strategy and asking Congress for enough money to execute it. That would include maintaining NASA’s annual Earth science budget at around US$2 billion and increasing NOAA’s annual satellite budget by $1-2 billion.

There’s a reason why space is called “the ultimate high ground” and our country spends billions of dollars each year on space-based assets to support our national intelligence community. In addition to national security, NASA missions contribute vital information to many other users, including emergency managers and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), farmers, fishermen and the aviation industry.

While NASA’s Earth observation satellites support numerous research scientists in government labs and universities, they also provide constant real-time data on the state of space weather, the atmosphere and the oceans – information that is critical to U.S. Navy and Department of Defense operations worldwide.

Six years ago while I was serving as oceanographer of the Navy, I was asked to estimate how much more money the Navy would need to spend if we did not have our NASA and NOAA partners. The answer was, very conservatively, $2 billion per year just to maintain the capability that we had. That figure has almost certainly increased. If the Trump administration cuts NASA’s earth science funding, that capability will need to come from some other set of agencies. Has the new team thought seriously about which agencies should have their budgets increased to make up this gap?

Finally a few thoughts about the elephant in the room: climate change. Mr. Walker has said that “we need good science to tell us what the reality is,” a statement virtually everyone would agree with. The way to have good science is to fund a sustained observation system and ensure the scientific community has free and full access to the data that these satellites produce.

Not funding observation systems, or restricting access to their data, will not change the facts on the ground. Ice will continue to melt, and our atmosphere and oceans will continue to warm. Such a policy would greatly increase risks to our economy, and even to many Americans’ lives. In the business world, this stance would be considered gross negligence. In government the stakes are even higher.

David Titley is a Professor of Practice in Meteorology & Director Center for Solutions to Weather and Climate Risk, Adjunct Senior Fellow, Center for New American Security, Pennsylvania State University

Environmental Action Archive

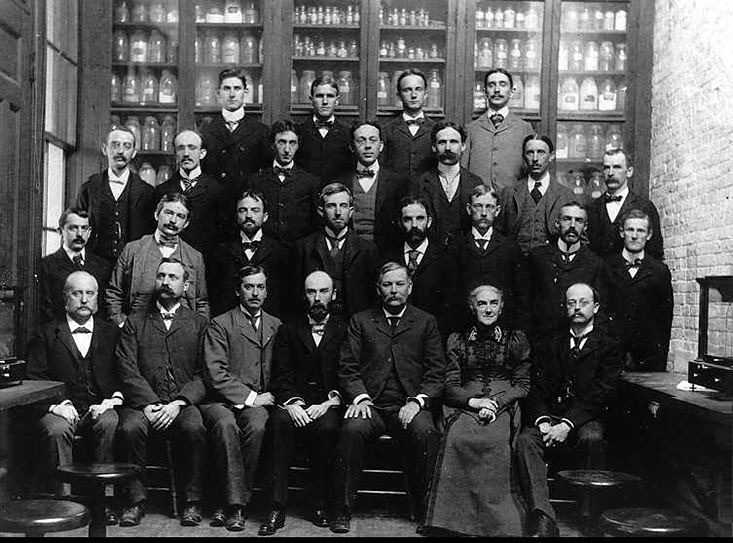

Environmental Action Archive Ellen Swallow Richards

Ellen Swallow Richards The hats that created bird sanctuaries

The hats that created bird sanctuaries  Pollution regs saved lives

Pollution regs saved lives ¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The

¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The ¶ Dymaxion car

¶ Dymaxion car  ¶ Aldo Leopold

¶ Aldo Leopold