One of the oil industry’s greatest historical myths is that petroleum arrived in 1861, just in time to light up the night and, as a bonus, save the whales from the whalers.

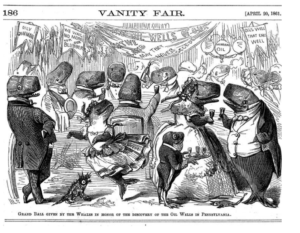

Even at the time it was something of a joke, as we see in this cartoon of whales celebrating the discovery of petroleum.

Oil industry historians took the joke seriously[1], and a century later, cracker barrel humor settled in as established history.

According to the myth: whale oil was running out, prices were going up, and the people wanted government intervention in the market. And yet, wisely, the government did not intervene and the free market soon found petroleum.

There’s just one problem: The myth is pure fiction. In fact, the US oil industry was created by subsidy, and not the free market.

The whale oil myth emerged in the 1970s, at a time when the Arab oil embargoes and other energy issues presented questions about government supply and price controls.

Walter Wriston, an influential conservative banker, used the whale oil shortage from the previous century in a 1975 speech to make the case for deregulating petroleum:

Naturally there were cries of profiteering and demands for Congress to ‘do something about it.’ The government, however, made no move to ration whale oil or to freeze its price… Instead, prices were permitted to rise. The result, then as now, was predictable. Consumers began to use less whale oil and the whalers invested more money in new ways to increase their productivity. Meanwhile men with vision and capital began to develop kerosene and other petroleum products.[2]

Wriston had no evidence to support these claims about profiteering or demands for legislation to protect whale oil. It was pure historical fiction, intended to buttress 1970s arguments for the deregulation of the petroleum industry. Democrats derided this use of fractured history, [3] but over the years, the myth took on a life of its own, and what began as an argument for petroleum industry deregulation in the 1970s found other uses.

- In 1988, for example, Burton Folsom used the whale oil myth to praise the virtues of Standard Oil and its generosity towards the impoverished masses: “Before 1870, only the rich could afford whale oil and candles… The rest had to go to bed early to save money. By the 1870s, with the drop in the price of kerosene, middle and working class people all over the nation could afford the one cent an hour that it cost to light their homes at night.”[4]

- In 1990, Daniel Yergin, historian and oil industry consultant, wrote: “For whalers [the 1850s] was the golden age. But it was not the golden age for their consumers, who did not want to pay $2.50 a gallon… An inexpensive, high-quality illuminant … [was] desperately needed.”[5]

- In 1992, conservative economist James S. Robbins applied whale oil to his argument against environmentalism in an essay, “Capitalism saved the whales.” Robbins said: “Stopping technology in its tracks in the 1850s would have doomed the whales. But suppose whaling had been outlawed then, as it is now? The immediate effect would have been a dramatic decline in quality of life.” [6]

- In 2008, economist Lester Lave said that whale oil “was the best way to get light at night. The problem was that there are only so many whales… So what happened was that in Western Pennsylvania, they discovered oil.”

- In 2010, Warren Meyer said in a Forbes article that the picture of John D. Rockefeller, founder of the Standard Oil Company, should hang on the wall of every Greenpeace office.[7] Through Rockefeller’s work, kerosene became both cheaper and safer to use than whale oil, and quickly began to replace it in the marketplace, and by the time the government stepped in to punish Standard Oil for being too successful, the whales had already been saved.

- Alex Epstein, an oil industry consultant, wrote in 2011: “In 1858, a year before the first oil well was drilled, only well-to-do families … could afford sperm whale oil at three dollars per gallon to light their homes at night. For most, the day lasted only as long as did the daylight. But by 1864… [people could] occupy a portion of the night in reading and other amusements.”[8]

- And in February of 2014, conservative columnist Michael Medved tried on the whale oil myth: “The story (about the whales) should reassure present-day pessimists of the near miraculous power of technological advancement and pursuit of profit to save the environment.”

Historical perspectives in conflict

On the surface, the economic lesson is simply that free markets work, and that high prices for one commodity will naturally lead to the search for alternatives. That’s reasonable.

But things are not so simple from the historical perspective. First, none of the literature of the era[9] shows complaints about scarcity of whale oil and its price. The idea that only the rich could afford light in the evenings is completely unsupported. In fact, there were plenty of affordable fuels on the market long before petroleum. There was no “dramatic decline in the quality of life” as Robbins and Folsom and Yergin claimed. Whale oil was one way, but not the only way, to get light at night.

Long before kerosene, inventors experimented with improvements on candles and simple lamps. Thomas Jefferson brought one of the new Argand lamps back from France in 1789, for example. But the combinations of lamps and fuels that became available in the very early nineteenth century presented new technical problems. Many vegetable oils were too viscous (thick) to effectively travel up a cylindrical wick (using the capillary “Cardano” effect), and they smoked when the wicks fell out of adjustment.

By the 1820s, inventors were turning to mixtures of natural hydrocarbons, especially distilled ethyl alcohol and turpentine. A Boston merchant, Howard Porter, patented the first US recipe in 1834 and marketed it as Porter’s Patented Burning Fluid. It was one the most successful lamp fuels on the market, and it influenced many other inventors.

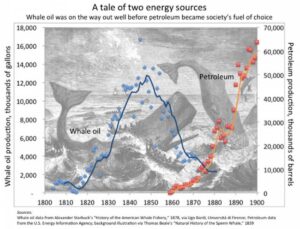

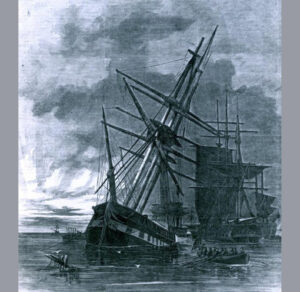

By mid century, what was really happening [11] is that whale oil production had peaked at 12 million gallons per year, and dropped to less than half that by 1860, according to Starbucks History of the American Whale Fishery.[12] The future of whaling was so dismal that President Abraham Lincoln had 38 decrepit whaling ships towed from New England whaling ports, filled with stone and deliberately sunk at the mouth of Charleston SC harbor. Whaling was dying long before kerosene, and could only contribute to the Civil War “stone fleet” blockade.[132]

The decline in whale oil production did not and could not have led to a dramatic decline in the quality of life. Before 1861, many different kinds of burning fluids and new types of lamps were coming on the US and European markets. “The use of burning fluid in the US as an illuminating agent, in places where coal gas was not available, was almost universal,” according to the US Internal Revenue Service. [10]

After 1862, a tax of $2.10 per gallon imposed on the alcohol beverage distilling industry and neglected to exempt industrial alcohol. With the main competition suddenly hobbled, the petroleum industry rushed in. The tax “had the effect of upsetting [the distilleries] and in some cases destroying them,” said IRS commissioner David A. Wells in 1872.

So: The birth of the oil industry was not a triumph of the free market, but rather, a direct result of government intervention in the marketplace. Petroleum did not emerge through competition between the fading whale oil market and kerosene.

The US government created the oil industry with a federal tax on fuels that had already been in competition with whale oil, especially alcohol, which was a necessary ingredient in camphene and burning fluids.

Why are we stuck with this myth?

First, very few of the serious histories of energy or petroleum have been written without the active engagement and financial support of the oil industry itself. The most significant histories of petroleum, including Daniel Yergin’s “The Prize,” (1992), Joseph C. Robert’s “Ethyl” (1984), H.F. Williamson & Arnold Daum’s “American Petroleum Industry” (1959), and Paul Giddens “Birth of the Oil Industry,” (1938), were written by academics using grants from the oil industry or by consultants who were already working in the energy business. So the historical business of petroleum is something of an echo chamber, with pro-industry historians building on each other’s mistakes.

Secondly, energy historians treat petroleum as a case apart, ignoring the alternatives and the broader historical questions and context. Energy histories often focus on what historian John Staudenmier calls “success stories.” The transition from whale oil to petroleum is viewed as the main narrative because petroleum was transcendentally successful until the late 20th century. This is called “whig history.”

The whig history of petroleum always places that industry at the center of events and everything else at the margins, at best. The idea that kerosene was a great benefit for the poor or somehow pre-ordained as the only fuel for the downtrodden masses is pretentious and counter-intuitive.

In fact, natural illuminating oils and candles were the byproducts of farms, sawmills and slaughterhouses, employing people and creating income within agricultural societies. It could just as easily be argued that the intrusion of petroleum into markets for these non-food farm products weakened agricultural economies at the dawn of the industrial age, just as it was argued in the early 20th century that the use of automobiles meant a loss of markets for horse transportation and a weakening of agriculture — for better and for worse.

In any event, serious historians cringe at fantasy, obfuscation and over-simplification, and most of the existing histories of petroleum fall heavily into these categories.

The idea that the whale oil myth could be taken so seriously, for so long, demonstrates the power of the oil industry to shape its own narrative, to possess its own history, and to exercise hegemony over the discussion of its past, present and, of course, its future.

As Milton Friedman once said: “Few industries sing the praises of free enterprise more loudly than the oil industry. Yet few industries rely so heavily on special government favors.”[14]

Footnotes

[1] Paul H. Giddens, Standard Oil Company (Indiana): Oil Pioneer of the Middle West (New York: Appleton Century Crofts, Inc., 1983); also H.F. Williamson and A. R. Daum, The American Petroleum Industry: The age of illumination, 1859-1899 (Northwestern University Press, 1961).

[2] Wriston, Walter B.. The Whale Oil, Chicken, and Energy Syndrome, The Economic Club of Detroit, Feb 25, 1974

[3] In a 1978 speech to the American Stock Exchange, Sen. Henry Scoop Jackson (D-WA) said the idea behind deregulation was “the same old whale oil myth … They say they dont want regulation. But what about the Conelly Hot Oil Act? What about import quotas? If that’s not regulation I’m stupid.”

[4] https://fee.org/articles/john-d-rockefeller-and-the-oil-industry John D. Rockefeller and the Oil Industry by Burton W. Folsom Foundation for Economic Education Oct 1, 1988

[5] Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, & Power. New York: Free Press.

[6] James S. Robbins, “How Capitalism Saved the Whales,” Foundation for Economic Education, Aug. 1, 1992.

[7] Warren Meyer, “The Man who Saved the Whales” Forbes, Nov 5, 2010.

[8] Alex Epstein, Vindicating Capitalism: The Real History of the Standard Oil Company (Part I: The Fallacious Textbook Story) August 29, 2011

[9] A search of ProQuest Historical Newspapers 1858 – 1864 turned up over 200 articles about whale oil but no commentary or editorials complaining about price, scarcity or demands for Congressional action.

[10] David Ames Wells, Recent Economic Changes, and Their Effect on the Production and Distribution, Philadelphia, PA D. Appleton & Co., 1890. P 33-34.

[11] In the words of historian Leopold Von Ranke, vie est eigenshaft gvessen

[12] Alexander Starbuck, History of the Whale Fishery, 1875

[13] The Stone Fleet https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stone_Fleet

[14] Milton Friedman, quoted in Oil policy and the environment, American Heritage Magazine, Aug. 1970, 21:5.

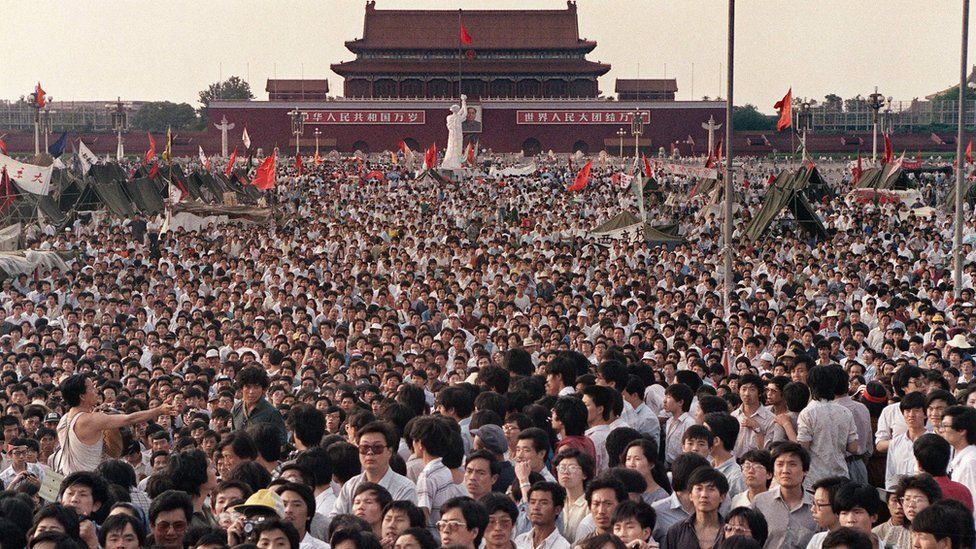

Tiananmen Square protests crushed

Tiananmen Square protests crushed  Ford Quadracycle

Ford Quadracycle

Ixtoc I Oil Disaster

Ixtoc I Oil Disaster

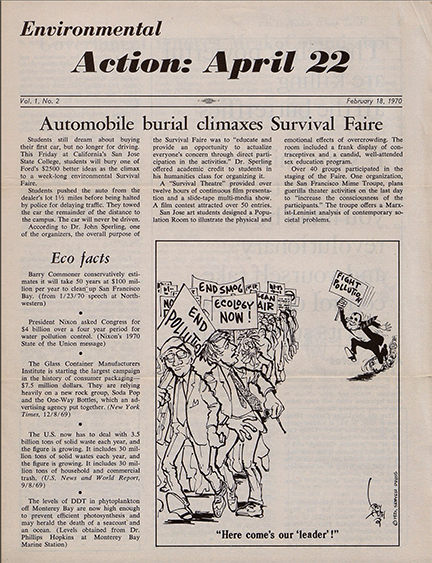

Environmental Action Archive

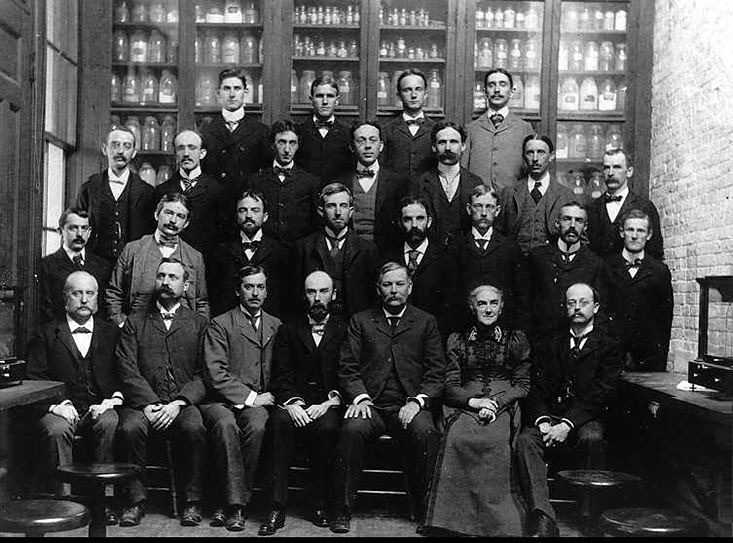

Environmental Action Archive Ellen Swallow Richards

Ellen Swallow Richards The hats that created bird sanctuaries

The hats that created bird sanctuaries  Pollution regs saved lives

Pollution regs saved lives ¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The

¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The ¶ Dymaxion car

¶ Dymaxion car  ¶ Aldo Leopold

¶ Aldo Leopold