By Mark Neuzil and Bill Kovarik in Mass Media and Environmental Conflict (Sage, 1996).

By Mark Neuzil and Bill Kovarik in Mass Media and Environmental Conflict (Sage, 1996).

Also See: Report on the Big Trees of California USDA (1900); Guardian newspaper (2013): and Wikipedia entry

In the middle of the 19th century, many citizens of the United States knew that California meant one word: gold.

The discovery of nuggets in a creek near Sutter’s Mill in 1849 and the rush of miners, businessmen, laborers, scalawags, hustlers, tinhorns and journalists thrust the new state into the country’s consciousness with the fever carried by precious metal. News accounts highlighted gold strikes, outrageous claims and great fortunes made and lost.

Back East, at the center of power, these news reports were important, because a trip to California for a first-hand look was difficult at best and life-threatening at worst. The country was a couple of decades away from transcontinental railroads: an overland passage could take four months or more and remained full of hardships; the sea route around South America was faster, but risky and expensive.In the 1850s, Americans learned about California through the pages of newspapers and magazines. A businessman named George Gale and his partners provided the nation with its first big news story from California after the gold rush. In the process, Gale and his companions inadvertently assisted the forces that led to the protection of the natural wonders of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. Gale’s vaudevillian stunt, which received press attention in the United States and Europe, has since slipped into the forgotten pages of history, but its byproduct, the national park system, lives on.

The story begins in 1852, when miners looking for another lode in the boom-and-bust cycle of their existence stumbled across a grove of giant trees in a remote mountainous area in Calaveras County in northern California. In a moment of unimaginative nomenclature, the miners named the area the Calaveras Grove of Big Trees. Native American tribes knew of the region, of course, and white hunters saw the Calaveras giant trees in 1850. The Sierra region had received local publicity in 1851, when a battalion under trader James Savage invaded a valley south of Calaveras in Mariposa County, in a skirmish with a tribe of Indians, the Ahwahnechee. Savage accused the tribe of raiding his trading posts and he and his men burned out the Indians, who escaped under the leadership of a brave named Tenaya. A surgeon in the battalion, Lafayette Bunnell, took time from his duties to serve as a diarist for the trip and he remembered the scenery. “It seemed to me I had entered God’s holiest temple, where that assembled all that was most divine in material creation,” he wrote several years later. A second expedition, under John Boling, caught up with Tenaya and his band in May of 1851, killing one of Tenaya’s three sons. The following spring, the Indians attacked a group of miners, killing two. The regular army invaded the valley, killing five captive Indians. Newspaper stories of the battles in the valley, which was called by the Indian name Yo-Semite, did not travel beyond California. Meanwhile, rumors of a second grove of giant trees near Yo-Semite, bigger and more numerous than the Calaveras Big Grove, circulated among the local population.

As word of the huge trees in Calaveras County spread among folks scratching out a living in the region east of San Francisco, among those who rode out for a look was Gale. Some 20 or 30 miles from the mouth of the Klamath River, Gale stumbled into the grove. Among the 92 giant sequoias in the 160-acre valley, Gale saw what he mistakenly thought was a cedar tree — not just a backyard cedar, but a tree measuring 300 feet high, 92 feet in circumference at the ground and perfectly symmetrical from base to top. He called it “the Mother of the Forest,” and sent to town for a team of five men to chop it down.

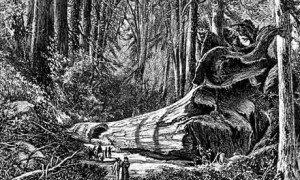

Gale was not a lumberjack, nor did he own a sawmill or a lumberyard. He was about to become involved in show business, and in the tree he saw the biggest attraction of his career. But the Mother of the Forest did not die easily. After Gale’s men bored holes through the trunk of the giant sequoia with a long auger, they worked saw blades from one hole to the next. The sawyers, cautious of a 300-foot tree falling on them without notice, continued with great care. The five men worked 25 days to complete the task. According to one account of the event, the tree was so “straight and balanced” that it remained upright, even after it was sawed completely through. Wedges were forced into the cut with hammers and sledges; the trunk was smashed by a crude battering ram, fashioned from nearby lumber, but the Mother of the Forest did not topple.

Not until a wicked gale blew up, in the dead of night (June 27, 1853), did the tree begin to “groan and sway in the storm like an expiring giant and it succumbed at last to the elements…” Sounds of the crash of the giant sequoia carried 15 miles away to a mining camp; the tree buried itself 12 feet deep into the muck of a creekbed. Mud from the creek splashed 100 feet high onto the trunks of nearby trees. Later, forestry experts in the East estimated that the sequoia tree was 2,520 years old.

Gale’s men stripped most of the bark — which was two feet thick in places — in sections, so it could be pieced together like a grainy jigsaw puzzle for display in the sideshow. Reassembled, the bark section was 50 feet high, 30 feet in diameter and 90 feet in circumference. Another portion of the tree was cut across the diameter, showing rings representing forest fires, drought and rainy seasons over the previous two-and-a-half millennia. Stripping of the bark was done “with as much neatness and industry as a troop of jackals would display in cleaning the bones of a dead lion.” The rest was left to rot. The tree was so immense — and stored enough water in its system — that five years passed before its leaves turned brown and died. Gale shipped the bark to Stockton, on its way to San Francisco, then to the Atlantic States and finally London, to be seen “for a trifling admission fee.”

Sadly for Gale and his partners, reaction to the tree was of two kinds, and both doomed the sideshow. Citizens either thought the bark to be a fake, or, more surprisingly, were hostile to the killing of what was billed the largest tree in the world. The editors of Gleason’s Pictorial, a widely read magazine pub

lished in Boston, said, “To our mind, it seems a cruel idea, a perfect desecration, to cut down such a splendid tree… what in the world could have possessed any mortal to embark in such a speculation with this mountain of wood?” Europeans cherish such trees, the editors said, and protect them by law. They hoped that two other American natural wonders, Niagara Falls and Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave, would be safe from purchase and exploitation, and wryly asserted that the cave “is comparatively safe, being underground.” New York newspaperman Horace Greeley, after visiting the region a few years later, wrote, “…it is a comfort to know that the vandals who bore down with pump augers the largest of the Calaveras trees, in order to make their fortunes by exhibiting a section of its bark at the east, have been heavy losers by their villainous speculation.”

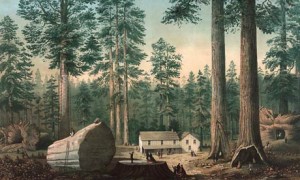

Economic speculation in the Calaveras Grove did not end with the bark exhibition, however. Another entrepreneur, seeing a tourist opportunity in the rugged hills 240 miles from San Francisco, built a hotel next to Mother of the Forest. The Mammoth Tree Hotel opened for business in 1855, with dances and theatrical performances held on Mother’s stump. Several dozen feet of the fallen tree’s surface were shaved flat; a tavern and two bowling alleys, complete with 81-foot lanes, were built on the leveled area and soon were ready for customers. Tourists also traveled to another, larger tree in the grove called Father of the Forest that had died a natural death many years earlier; its corpse ran along the ground for 450 feet and, after a rain, held a pond in its trunk deep enough to hold a steamboat.

The publicity surely stimulated interest in the natural wonders of California. Historian Hans Huth said vandalism such as the killing of the Mother of the Forest caused Easterners to ponder their duty to protect nature. A more recent environmental historian, Donald Worster, insightfully argued that ecological thought reflected not just discoveries (such as the Mother of the Forest) but the specific cultural conditions in which those discoveries arose. For example, the excitement caused by the felling of the giant tree caught the attention of one of the country’s most popular philosophers and poets, James Russell Lowell. In an article for The Spectator, reprinted in other publications, the well-known social critic called for a society for the protection of trees. “The American seems to have an hereditary antipathy to Indians and trees, both having been the foes he had to first encounter in conquering himself a home here in the West,” he wrote. Lowell, who had succeeded Henry Wadsworth Longfellow as chair of modern languages at Harvard, wanted trees to be left alone, free of the interference of sideshow huckster and government forester alike. “That is the best government for trees which governs least…” he wrote. “Nature knows better than any city forester.” Lowell’s dislike of government foresters prevented him from extending his minimal interference notion to the idea of state protection. The idea had been on the books as early as 1817 in the United States, when the Secretary of Navy was authorized to reserve lands producing oak and cedar for the purpose of supplying lumber for ships.

In 1864, 11 years after Gale felled the Mother of the Forest and seven years after Lowell’s call for a tree protection society, the federal government granted the State of California an area of about eight square miles to be used as a park several miles south of the Calaveras Grove of Big Trees. Ironically, the Calaveras Grove of Big Trees was left out of the protected area, even after all the attention it received in the popular press. The new park was in Yosemite Valley, which was home to more giant trees — the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees, plus spectacular and unusual granite formations, delicate waterfalls and scenery unlike any other in the world. The process of making Yosemite Valley a park, which began with the discovery of the Mother of the Forest, worked its way through the political arena with unusual speed. Yosemite Valley provided a model for a new kind of land use, a state park, which was to be joined by another model — a federal park — at Yellowstone eight years later.

SEEDS OF THE PRESERVATION IDEA

If one uses the works of writers such as James Russell Lowell as evidence, the seeds of environmental thought in the United States were in place by the end of the Civil War. Two of Lowell’s contemporaries, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, played critical roles influencing the early environmental movement. Both had written and circulated significant works on the appreciation of nature before the end of the Civil War. Emerson wrote of the outdoors in 1836: “…in the wilderness, I find something more dear and connate than in the streets or villages… in the woods we return to reason and faith.” Thoreau was more specific in his writings, particularly in his private correspondence: “National preserves, in which the bear, and the panther, and some even of the hunter race may still exist, and may not be civilized off the face of the earth — not for idle sport or food, but for inspiration and our own true revelation,” he wrote in 1858. Thoreau’s Walden, published in 1854, became a significant text for environmentalists in the 20th century.

While Thoreau and Emerson were writers first and foremost, Lowell later served as ambassador to England and to Spain. His political interests were shared by George Perkins Marsh, a Vermont lawyer, U.S. representative and ambassador to Italy. In 1864, near the end of his career, Marsh wrote a book called Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Condition. In the book, Marsh said of the human condition “…the earth is fast becoming an unfit home for its noblest inhabitant.” Further, Marsh noted the need to preserve “American soil… as far as possible, in its primitive condition.” A preserve could be “a garden for the recreation for the lover of nature.” The national trend was in the other direction, however, as laws such as the Homestead Act of 1862 virtually gave land away to anyone with a small bank account and a desire to make a go of it on the frontier. Unscrupulous developers used the law to snatch large plots of land and resell them at enormous profits.

While Lowell, Marsh and Thoreau were aware of the western half of the nation, their personal lives did not include extended stays in the vast areas of the frontier. The task of conveying first-hand experiences of the West fell to explorers and storytellers like Daniel Boone (through his biographer, John Filson), Osbourne Russell, Francis Parkman and John Wesley Powell. Artists such as George Catlin worked in the Mississippi Valley from the 1830s; some historians credit Catlin with originating the preservation idea in 1833, although it is not clear whether he intended a protected reservation to be home for Indian tribes or as a national park for preserving nature.

A major in the Army who lost an arm at the Battle of Shiloh, Powell is probably most well-known for his 1869 rafting expedition down the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. Magazines and newspapers of the day carried accounts of the expedition, including articles written by Powell. He later became familiar to readers of Scribner’s Monthly after a series of his stories appeared in 1874 and 1875. Other writers contributed to and reflected the national mood. Popular fiction writer John Burroughs’ first nature essay, “With the Birds,” appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in 1865, with many more stories to follow until his death in 1919. By 1880, a writer for Harper’s said that parts of the Rocky Mountains were becoming too popular with the press, crowded with visitors and immodestly advertised.

On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law an act designating over two million acres of what is now northwestern Wyoming and parts of Idaho and Montana as Yellowstone National Park. In the words of national park historian John Ise, Yellowstone was “so dramatic a departure from the general public land policy of Congress that it seemed almost a miracle.” Prior to the creation of Yellowstone, there had been two other instances of U.S. governmental protection of wild or unusual lands. The first case came in 1832 with the establishment of the Arkansas Hot Springs as what was called a national reservation. Clearly, the rejuvenating waters of Hot Springs were saved not as a park, but because they were “thought to be valuable in the treatment of certain ailments.” The second instance was the state model at Yosemite Valley.

THE YOSEMITE MODEL

On May 17, 1864, Congress enacted legislation that withdrew two tracts of land in Mariposa County from the public domain and transferred them to the state of California. Congressmen were familiar with the Yosemite region, having had the opportunity to read several accounts of the area in Eastern newspapers after the stir caused by the Mother of the Forest exhibition in the 1850s and subsequent visits by leading Eastern newspapermen. In 1856, a New York magazine called The Country Gentleman reprinted an article from a California journal extolling the natural beauty of the Yosemite region, “the most striking natural wonder on the Pacific.” Other California publications wrote of the area, and, in the manner of the day, Eastern newspapers and magazines excerpted bits and pieces of the articles. Artists visited Yosemite, including Thomas A. Ayres, a Californian whose lithographs toured the East. A travel guide published in 1857 included a brief section on Yosemite Valley.

One newspaperman who legitimized the idea of Yosemite Valley as a paradise worthy of protection by the state was Horace Greeley. The New York Tribune publisher and editor, well-known for extolling the virtues of the American West, visited the area in a highly publicized trip in the summer of 1859. Many historians mention Greeley’s trip as a key event in the protection of the area, but an examination of the popular editor’s notes shows a somewhat less glamorous experience than the myth that grew out of it.

Starting out from Sacramento, Greeley and his companions took the stage to Stockton, where they rested before a 75-mile carriage ride to Bear Valley in heavy August heat. As they bumped their way into the mountains, the group crossed the waters of the Stanislaus, Tuolumne and Merced rivers, all rendered a churlish brown by the mining operations in the hills. Over the objections of the natives, Greeley left Bear Valley for Yosemite at 6 a.m. on an arduous horseback trip (in a saddle with a Mexican stirrup that was too small for his left foot) “not having spent five hours on horseback… within the last 30 years.” His guide was Hank Monk, whom Mark Twain later highlighted in his book, Roughing It, for his hell-bent and hurried pace.

The middle-aged editor made the entire trip in a single day, but did not arrive in the valley until long after dark “riding the hardest trotting horse in America.” The bad stirrup caused his foot to swell, making walking impossible, so he had to remain on horseback in the roughest terrain while other members of the party led their horses. The descent into the valley on the three-mile-long, steep, single-file trail took two hours under moonlight. Reaching a cabin after 1 a.m., Greeley went to bed without food or drink. Covered with boils from the trip, he estimated he had ridden 60 miles and climbed and descended 20,000 feet.

Greeley, stiff with age and travel, arose “early,” rode in the valley, dined at 2 o’clock and left. Despite the brevity and hardship of his visit, the journalist was unsparing in his praise of the region: “I know of no single wonder of nature on earth which can claim superiority over Yosemite.” He called on the state of California to protect the big trees, “the most beautiful trees on earth.” The mountains “surpass any other mountains I saw in the wealth and grace of their trees.”

The eastern newspapermen, writers and artists initiated a sometimes uneasy business/intellectual union that continued in environmental issues through the 20th century. Beyond being a journalist, Greeley represented the major Eastern business establishment, and saw economic possibilities in westward expansion and land and mineral development. Many people, including other journalists, noted his reports in the New York newspaper. The next significant publicity Yosemite received came from the pen of Thomas Starr King, a well-known Eastern author and journalist who had moved to San Francisco in 1860. Starr King wrote a series of eight articles from December 1860 to February 1961 for the Boston Evening Transcript. Starr King’s articles, which were intended to be reprinted as a book, were full of lavish descriptions of the region and its wonders, including the sequoias, the mountains and the valley. Starr King died in 1864, remembered as a champion of the region. One of the giant sequoias, measuring 366 feet tall, was named after him.

Media coverage made many, include some members of Congress, aware of the unique nature of the Sierra region. Senator John Conness of California introduced a bill to protect the Yosemite Valley in March of 1864. President Lincoln signed the measure in June. There is little recorded debate over the measure, leaving an aura of mystery surrounding the process. One congressman asked Conness about the size of the property, and he was told the Mariposa Big Tree Area, as it was called, was “about a mile.” Conness also said that “certain gentlemen in California, gentlemen of fortune, of taste, of refinement” suggested the bill to him. Conness did not name the gentlemen, but it is likely that state geologist J.D. Whitney, Judge Stephen Field, Professor John F. Morse, businessman Israel Ward Raymond and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted (designer of New York’s Central Park) were among them. During the debate, the senator recalled the death of the Mother of the Forest, and he was clear in his intent to protect the trees: “The object of this bill is to prevent their being cut down or destroyed.”

Historians have debated how and why the national parks were created, but the establishment of each park should be examined in its own social and cultural context. Certainly the increase in leisure time in society after the mid-19th century played a role in the development of some parks, including Yosemite Valley, which did not appear to have much economic use in an agricultural or mineral sense. Preserving the unusual big trees and other unique scenery was another factor. Historian Alfred Runte said Congress protected only “economically worthless” lands — or lands Congress believed to be economically worthless — and the source of this belief may have been park supporters, who may have seen it as a way to get legislation passed amid the unbridled capitalism of the 19th century. Why the Yosemite land was deeded to the state is another matter of speculation. In the end, the deeding may have been judicious. Perhaps the lax enforcement and loose provisions of federal land laws would have made it easier for homesteaders and land speculators to snatch pieces of Yosemite property. The grant was given “upon the express conditions that the premises shall be held for public use, resort and recreation and shall be held inalienable for all times.”

The formation of the park increased the public’s interest in the area. After Lincoln signed the bill, Springfield Republican editor Samuel Bowles and noted war correspondent Albert B. Richardson of the New York Tribune were in a parade of journalists who journeyed to Yosemite. Bowles and Richardson visited the area with Speaker of the House of Representatives Schuyler Colfax and 18 people over four days in August of 1865. Upon seeing the region for the first time, Bowles wrote, “All that was mortal shrank back, all that was immortal swept to the front and bent down in awe.” The visitors saw an area home to nine species of pine, two of silver fur, and five other conifers, plus oaks, maples, poplars and others. Olmsted, the first commissioner of the park, was seeking more state funds for the valley, and Bowles wrote in support of the park idea. Yosemite, he said, “furnishes an admirable example for other objects of natural curiosity and popular interest all over the Union.” The park idea was popular. Bowles reported the number of visitors to the valley grew to 300 in the first seven months of 1865, up from 100 for all of 1864. The journalist suggested similar state government protection for Niagara Falls, the Adirondacks and a Maine lake and its surrounding woods. Richardson echoed those sentiments in a report published on the trip in 1867.

THE YELLOWSTONE MODEL

In the Reconstruction years, laissez faire economics represented the dominant ideational model as the country underwent an unprecedented period of business and industrial growth. Technological innovations in communication and transportation were making the nation known and conquered. Unrestricted competition was the rule of the day. With the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad in 1869, the West and all of its natural resources — for ranching, mining, timber and farming — opened on a gigantic scale. Further, progress became “synonymous with growth, development and the conquest of nature. The idea of living… harmoniously with nature was incompatible with 19th century American priorities.”

The protection idea was revisited in 1872, but not at Niagara Falls or in Maine, as Richardson had hoped. Instead, Congressional leaders acted to preserve Yellowstone Park in the mountains of the Western territories. Unlike the Yosemite model, however, no state government existed to assume title to the land, so a federally controlled national park may have been seen as the only solution. In March of 1872, President Grant, who would run for reelection against Horace Greeley in the fall, signed the Yellowstone National Park Act. Evidence suggests a coalition of media, railroad companies, government scientists and conservationists led to its establishment. The signing of the Yellowstone bill was uncharacteristic of President Grant, who was no particular friend of the wilderness, nor did he favor federal intervention in any matter, much less conservation. For example, in 1875 the nation’s first wildlife protection bill (including a measure designed to protect the vanishing buffalo herds of the West) passed Congress, but Grant vetoed the proposal. Congress failed to override the veto and 10 years later the buffalo were all but gone from the Plains.

Occupied by members of the Shoshone, Blackfoot, Bannock and Crow tribes in the early 19th century, Yellowstone was explored by white trappers in the 1830s, including Osbourne Russell. A number of public and private expeditions explored the area from 1869 to 1872. The fledgling conservation idea, defined and publicized by writers and journalists, joined with major business interests and the government at Yellowstone in the person of U.S. geologist F.V. Hayden, who was a prominent park supporter. Hayden traveled to Yellowstone in 1871, collecting geologic samples in his role as government scientist; on the same trip he surveyed the area for the Northern Pacific Railroad. Hayden, a physician, had “strong friends in Congress and the railroad lobby” and received $40,000 for his Yellowstone trip from Congress for a geologic survey of “the sources of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers.” The 20-man survey party included landscape artist Thomas Moran, who was in the employ of the railroad. Moran’s job was to paint the vistas of the proposed park; his works were part of the lobbying effort, as were the photographs of expedition member William H. Jackson.

Upon returning to Washington, Hayden urged passage of the Yellowstone Park legislation in the halls of Congress. Joining Hayden in the lobbying effort was Nathaniel Pitt Langford, a Montana politician and among the 19-member Washburn Expedition of 1870, another Yellowstone trip partially funded by the railroad. Both Hayden and Langford wrote articles for the popular magazine Scribner’s Monthly urging passage of a national park bill and favorably mentioned the railroad. Langford, who would become the park’s first superintendent, wrote of a two-month trip to the region in the May and June 1871 issues of Scribner’s. The majesty and grandeur of what Langford and his party saw enchanted them, while at the same time the men were frightened by the unknown qualities of geysers, mud lakes and sheer precipices. Langford was not so frightened as to miss the possible economic benefits of the area, however. “By means of the Northern Pacific Railroad, which doubtless will be completed in the next three years, the traveler will be able to make the trip to Montana from the Atlantic seaboard in three days, and thousands of tourists will be attracted to both Montana and Wyoming in order to behold with their own eyes the wonders here described.” Coming upon the gigantic rock formation later called Devil’s Slide, Langford wrote: “In future years, when the wonders of Yellowstone are incorporated into the family of fashionable resorts, there will be few of its attractions surpassing in interest this marvelous freak of the elements.” The Washburn Expedition shot venison, grouse, antelope and deer and caught and dried several hundred brook trout for provisions along their journey.

Langford, a descendent of Salem, Mass., settler John Langford, was a native of New York who came to St. Paul, Minn., in 1854 to work as a banker. He continued west in 1862, becoming tax collector for the Montana territory. A politician, he was appointed territorial governor of Montana, but was never seated due to a dispute with President Andrew Johnson. One of his friends called him “the John the Baptist of the National Park idea, crying aloud both in the wilderness and out of it…” Another leader of the Yellowstone trip, a Harvard-educated judge named Cornelius Hedges, was an Easterner by upbringing, prompting one historian to write: “The men who were responsible for conceiving the national park idea and pushing it through Congress in 1872 were, without exception, nature importers from eastern states.” Local residents were slow coming around to the idea of a park “until it became clear that Yellowstone Park would attract money-spending tourists. The realization that park development might help, rather than hinder, development, won over the locals.”

Langford’s descriptions of the natural wonders of Yellowstone inspired Hayden to travel to the region the following year. Hayden detailed his journey in Scribner’s Monthly of February 1872 in an article called “More About Yellowstone.” While Hayden’s article mainly spoke of the unique geologic nature of the region, claims by a couple of homesteaders in an area of hot springs also caught his eye. “With a foresight worthy of commendation, two men have already preempted 320 acres of land covering most of the surface occupied by the active springs, with the expectation that upon the completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad this will be a famous place of resort for invalids and pleasure-seekers.” Hayden urged Congress to act to make a park, although how he thought a park could co-exist with homesteading is unclear. Hayden wrote:

“The intelligent American will one day point on the map to this remarkable district with the conscious pride that it has not its parallel on the face of the globe. Why will not Congress at once pass a law setting it apart as a great public park for all time to come, as has been done with that not more remarkable wonder, the Yosemite Valley?”

A few weeks after Hayden’s article, President Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Act. Unknown to the general public, Langford and Hayden were in the employ of the railroads. Jay Cooke, owner of the Northern Pacific Railroad, partially funded Langford’s Washburn Expedition and sponsored Langford on a 20-lecture tour in the eastern U.S. Hayden heard a Langford lecture in Washington, D.C., and was inspired to travel to the park; soon Cooke asked him to survey the area for a railroad.

When the park bill was up for debate, the railroad, in a “lobbying blitzkrieg,” engaged Hayden and Langford to set up shop in the capitol rotunda, displaying geologic samples, Moran’s sketches and photographs of the area taken by Jackson. Congressmen received copies of Scribner’s Monthly. The railroad company “quite probably paid the expenses necessary to insure a speedy passage of the park bill through Congress.” After formation of the park, the railroad funded the first concessionaire fees and Langford was named the park’s first superintendent, though he was not paid. A coalition of media, business, government and conservation members was born.

Following the creation of the park, Scribner’s praised the act in May 1872, noting the utilitarian value of the property, in keeping with 19th century values. Calling the area a “pleasure ground” and “junketing-place,” the anonymous author of the article said the park “aims to ensure that the region in question shall be kept in the most favorable condition to attract travel and gratify a cultivated and intelligent curiosity.” Noting the flow of Americans to Europe on vacations, the magazine went on to point out “when the Northern Pacific railway, as we are led to hope to be the case, drops us in Montana in three days’ journey, we may be sure that the tide of summer touring will be perceptively diverted from European fields. Yankee enterprise will dot the new park with hostelries and furrow it with lines of travel.”

The Yosemite model, coming in a call to save 2,000-year-old trees, may or may not have been carried out for idealistic reasons, but the Yellowstone model was definitely in keeping with the economic views of the day, primarily the relatively new business of tourism. Placing the park under federal protection was a departure from the Yosemite idea, and it left the nation with a pair of experiments.

THE 1890 YOSEMITE EXPEDITION

Yellowstone represented an alternative to the Yosemite model and both were tested by economic and political pressures buffeting the parks in their formative years. Yosemite’s overseers, the California Commission to Manage Yosemite Valley, met only a few times a year to supervise park operations. The first commissioners on the eight-member board were genuine and straightforward in their dealings about the park, but politicians in Sacramento soon took control of the appointment process, beginning a period of mismanagement. In Yosemite, sheep (and to a lesser extent, cattle) overgrazed the land, while loggers raided the forests. In the 1870s and 1880s, many trees were felled, some only for their seeds. Hay planted in the valley fed the horses bringing tourists into the park after livestock chewed up much of the valley’s natural grasslands.

Yellowstone had its share of problems. The Department of Interior was charged with protecting and maintaining the property, but Congress did not provide money for upkeep nor enforcement provisions for poaching. Park officers ate park buffaloes, and unusual rock formations were quarried and sold for cash. Park superintendent Phileton W. Norris estimated that 7,000 big game mammals — elk, bighorn sheep, deer, antelope and moose — were killed in the spring of 1875 alone. One of the first concessionaires, the Park Improvement Company, signed a contract in 1882 with professional hunters to kill 20,000 elk, bison, deer and mountain sheep to feed its employees — because wild game was cheaper than beef.

Enter the cavalry. Administration of the park was turned over to the U.S. Army in 1886, and the military ran Yellowstone until the 1916 creation of the National Park Service. The Army cracked down on poaching, sent scouts to drive big game back into the park and put up several miles of 7-foot-high fencing to keep them there. Army details fed elk and antelope in the winter and left garbage for bears to forage. The army replaced the depleted stocks of native cutthroat and grayling with imported game fish from all over the world — German brown trout, Lake Superior salmon, Lock Levens from Scotland, brook trout and salmon from the eastern United States and coho salmon, rainbow trout and mountain whitefish from other Western regions. Soldiers also stocked black bass and yellow perch.

The Army had better luck replenishing animals than fish. Many of the salmon, rainbow trout and black bass died quickly; the brown trout crowded out the native species and the yellow perch in Goose Lake multiplied and were poisoned to keep the population under control. Meanwhile, most of the animals, particularly elk, bred and prospered. “The best service in forest protection — almost the only efficient service — is that rendered by the military,” wrote wilderness lover John Muir in his journal. “… Blessings on Uncle Sam’s soldiers. They have done the job well, and every pine tree is waving its arms for joy.” The Lacey Act of 1894, which prohibited hunting and trapping in the park, aided animal populations. For several years, the cavalry resisted political pressure from farmers, ranchers and the U.S. Biological Survey to kill predators — wolves, coyotes and mountain lions. The only mammalian failure was in the park’s mountain bison herd, which dropped to 25 animals by 1901. Plains bison were imported from Texas and cross-bred with the remaining mountain bison; a buffalo ranch was built and grains were planted for feed in some of the valleys. By 1912 the hybrid herd recovered. Yellowstone, particularly after the frustrated Interior Department turned protection of the park over to the Army, became representative of the federal centralization of power that marked the Progressive Era and its ideas about the conservation of natural resources.

As the Army got control of Yellowstone, the Yosemite Valley still bent under the political winds of the state of California. Six bills were introduced in Congress between 1879 and 1886 to expand the protection of the Yosemite region around the smallish California park, but all failed. Finally, in 1890, legislators created a one-million-acre federal reserve around Yosemite Valley. The Yosemite National Park amendment passed both houses of Congress in two days behind a coalition of railroad lobbyists and conservationists strikingly similar to the Yellowstone group.

Century magazine journalist Robert Underwood Johnson was an important figure in the 1890 Yosemite issue, along with the Boone & Crockett Club and the people who would create the Sierra Club, particularly Muir, who had become nationally known as a geologist through his magazine articles. Muir’s theories of the glacial activity in Yosemite gained fame after a series of articles in 1874-75 in Overland Monthly, which were “the first scientifically accurate description of the formation of the Sierra Nevada, and threw Muir to the forefront of the scientific world.” In addition to his work as a geologic theorist, Muir was well-known as a writer, philosopher and naturalist and an expert in publicity. Greeley hired him to write on the Yosemite Glaciers in the New York Tribune in 1871, the first of 65 newspaper and magazine articles he wrote over the next 20 years. A native of Scotland, his family emigrated to Wisconsin when John was 11 years old. He spent much of his young adulthood wandering North America, from Canada (where he went to avoid conscription during the Civil War) to Florida. By the 1860s, he journeyed into Yosemite, where he made a home until his death in 1914. A highly moral man, Muir saw the Creator in nature; he believed wilderness existed for its own sake, not necessarily to serve the needs of humans. Heavily influenced by Emerson and Thoreau, Muir spent most of his life attempting to protect wild places, and Yosemite was his passion.

Muir and the preservationists ran into trouble with three groups when they tried to set aside a Yosemite park in 1889: local entrepreneurs, e.g., the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company, which brought tourists from the railroad station to the park; cattlemen, sheepherders and loggers; and California politicians, who were under the influence of Leland Stanford, head of the railroad. Muir had been attempting to get parts of California preserved since the late 1870s; in 1881, he helped draft a bill based on the Yellowstone model to preserve the Kings River region in the southern Sierras, but it died in committee. Congress also stymied his attempt to enlarge the region around Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove (by giving more property to the state). Muir’s attempt to protect Mount Shasta met a similar fate in 1888.

Muir could not win legislative relief on his own. Johnson, Century’s associate editor, was emerging as a leading figure in the preservationist movement by 1890, and he had important friends in Congress. Johnson knew his way around Washington after he spent nearly two years successfully lobbying for an international copyright law in the late 1880s. As the park crusade heated up, Johnson wrote two articles in the January edition of Century. The lead article, titled “The Care of Yosemite Valley,” took the members of the Yosemite Valley Commission to task for a plan to chop down all trees less than 30 years old. Johnson, who took 100 pictures of the “mismanaged” park, wrote of “the moral claim of all humanity to an interest in the preservation of the wonders of the world.” The article contained the beginnings of a favorite theme of Century’s over the years, that of asking for turning control of the state park over to the national government. For these efforts, several California newspapers, many of which were indignant over the possibility of federal control of the entire Yosemite region, attacked Johnson and his friends. This was among the times that the media did not uniformly favor the park idea — California media supported local control of the park, while the media centered in the Eastern United States favored national control. This would be predictable, based on theoretical notions that mass media tend to represent their local interests first and foremost. On one level, the San Francisco newspapers represented the interests of the business and political elites of northern California; the Eastern newspapers and magazines would not be concerned about California per se, but their own interest groups and constituents who were interested in vacationing grounds and nature preservation.

Johnson talked Muir into writing two articles glorifying Yosemite for Century in August and September of 1890. Muir wrote in the manner of the transcendentalism of Emerson, who visited Muir at Yosemite in 1871, and Thoreau: “No temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite. Every rock in its walls seems to glow with life.” In describing one view from a mountain peak, Muir wrote: “[It is a] view that breaks suddenly upon you in all its glory, fair and wide and deep; a new revelation in landscape affairs that goes far to make the weakest and meanest spectator rich and significant even more.”

Muir also criticized the ability of the state commission to manage Yosemite Valley, where slapdash saloons, clapboard hotels and a fragrant butcher shop, complete with pigpen, stood cheek to jowl. Muir proposed an alternative. “Steps are now being taken toward the creation of a national park about the Yosemite, not only for the sake of the adjacent forests, but for the valley itself.” The following month, Muir was more specific. “The bill cannot too quickly become law,” he wrote. “By far the greater part of the destruction of the fineness of wildness is of a kind that can claim no right relationship with that which necessarily follows use.” In the same issue, a Century editorial also urged the passage of protective legislation. The editorial said “the Yosemite is too great a work of nature to be marred upon by the intrusion of farming operations or of artificial effects.” The editorial also criticized the commission when it claimed a “hope for the good name of the state that will not be necessary to transfer to the halls of Congress the scandals of California’s capitol.” Muir’s writing inspired Rep. William Vandever of California to introduce a park bill, while Olmsted wrote letters to newspapers urging its passage. Johnson appealed to a pair of influential politicians, Rep. William S. Holman of Indiana, a Democratic member of the House Committee on Public Lands and an old family friend, and Sen. Preston B. Plumb of Kansas, Republican chair of the equivalent Senate committee. Both men had clout: Holman was serving in his 26th year in Congress; Plumb was first elected in 1877.

The bill signed by President Harrison on October 1 was very different from the one introduced by Vandever in March as HR 8350. The bill did not come to the floor of the House until September 30, whereupon Vandever deftly substituted another measure, HR 12187. There was a major difference between the two bills, although the substitution happened with only a minor amount of political grousing. That difference was in the size of the proposed park — the substitute bill offered a park five times larger than HR 8350. The new bill looked suspiciously like a park proposal Muir made in 1889, although no congressman noticed it at the time. After passing the House, Plumb brought HR 12187 to the Senate floor the next day, the penultimate day of the session. Senator George Edmunds of Vermont raised the only protest to the bill, saying that he did not understand it. Someone drew Edmunds aside, spoke to him quietly, and he withdrew his objections.

No one ever admitted drafting the substitute bill, and the Congressional archives do not even contain the original bill. Who was behind the measure that increased the original park plan by five times, to 1,500 square miles? Circumstances point to the Southern Pacific Railroad. The critical moment may have come when Stanford, who rejected pleas for help from editor Johnson in 1889, was forced out as railroad president in favor of Collis Huntington, who announced that Southern Pacific was “withdrawing” from politics, perhaps as part of a public relations move. Huntington then may have directed Southern Pacific lobbyists to help Muir win approval of the park bill. Historian Stephen Fox said, “All but invisibly, so as not to burden the Vandever bill with the SP tarnish, the railroad’s lobby moved behind the measure.” The railroad’s reasoning may have been twofold — tourists and timber. At about the same time, Congress established Sequoia National Park and General Grant National Park — both areas were rich in timber, which could not have been logged and transported without the services of the railroad. The railroad also ran a spur to Raymond, one of the pick-up points for the Yosemite Stage and Turnpike Company.

In any event, Yosemite provided the conservation movement with an important victory. The cavalry was given charge of Yosemite, as it was in Yellowstone, and forced out the sheepherders. The model established by the Wyoming park wound up as the dominant system of large-scale land protection in the United States. At Johnson’s urging, the Yosemite campaign led to a permanent coalition of elite members of San Francisco society, as two University of California professors, William D. Armes and Joseph LeConte, joined with San Francisco attorney Warren Olney to form the Sierra Club in 1892. They persuaded Muir to become its first president.

THE RECESSION OF YOSEMITE VALLEY

Muir published a series of articles in the Atlantic that became the book, Our National Parks, in 1901. The Scotsman began to gather support for the idea of receding Yosemite Valley, which he called “frowzy and forlorn” in his journal, to the federal government. Among those he persuaded was President Theodore Roosevelt, with whom he camped in Yosemite in 1903, and California Governor George C. Pardee, both Republicans. Historians remembered the Roosevelt camping trip for the jubilance with which the president greeted the dawn after an evening’s snowfall, but events of the day also illustrated attitudes toward nature were different in the beginning of the century. Late one evening, when Muir and Roosevelt camped away from the rest of their party, Muir quietly arose from his bedroll and set fire to a tall, dead pine in a meadow. The tree erupted in flame. “Hurrah!” Roosevelt shouted. “That’s a candle it took five hundred years to make. Hurrah for Yosemite!”

A bill to recede the valley, drafted by a Sierra Club member, was introduced into the California assembly in early 1905, to heated debate. On one side were a few local newspapers and elected representatives of the valley’s business interests, who fought the “giveaway.” The Sierra Club, which began a letter and telegraph campaign, and Pardee’s administration took the opposite view. After passing the state House, the bill ran into trouble in the Senate in the person of Senator John Curtin, Democrat from Sonora. Curtin, an attorney for the stage-line and hotel interests in the valley, had once tried to graze cattle in the area. One of his arguments against recession was that firearms were not allowed in the national park. “I would not live under a government that would not let me carry a gun,” he said. One newspaper headline read: “Those Who Would Vote For Recession Of Yosemite Must Be Traitors.” Among the newspapers opposed to the recession was William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner, which resisted the idea of federal control of a state treasure. The Examiner printed petitions in December and January which the newspaper claimed resulted in 62,890 signatures protesting the recession plan. Hearst also fought the railroads at every turn, so any issue favored by Southern Pacific, Hearst reflexively would oppose. And with a very close vote looming, Muir appealed to the railroads for help.

The Southern Pacific had landed in the empire of New York financier E.H. Harriman, who had known Muir since an eventful 1899 trip to Alaska. Harriman financed the Alaskan expedition, which included Harriman and his family, Muir, John Burroughs and several dozen scientists, poets, photographers, hunters and artists. On the trip, Muir named a glacier in Glacier Bay after Harriman. “Mr. Harriman came to thank me for proposing the name,” Muir wrote in his journal. Six years later, Harriman agreed to help Muir in the Yosemite Valley matter. The railroad, the largest and most powerful political force in the country, again kept its role secret: Its legislators were told to speak out against the bill in the California Senate, then vote for it. “…California and the country are much indebted for the success of this [Yosemite] measure of retrocession to Edward H. Harriman.” Johnson wrote in his memoirs. The state Board of Trade joined the coalition by coming out in favor of the bill, to save itself the annual $13,000 appropriation for park upkeep. A sudden shift of a few votes allowed the measure to pass by a single vote.

The battle was not over, however. Congress required federal legislation to accept the receded grant. Muir and Johnson, with the railroad’s help, went to Washington to get Congress to act. State Senator Curtin and other stockmen worked to carve a slice of the park for grazing. Timber companies fought for a pair of rich groves of sugar pines; the city of San Francisco asked for water rights in the Hetch Hetchy valley and Lake Eleanor. Joseph Cannon, the powerful speaker of the House of Representatives, held up the bill because of its costs — more federal dollars would be needed for roads, maintenance, staff and other expenses.

Muir wrote Harriman, asking him to get involved. The railroad magnate penned a personal letter to Cannon, enclosing a copy of Muir’s letter. Cannon reversed field and the acceptance bill passed the House in May. In the Senate, the bill stumbled again before Harriman applied more pressure and Roosevelt announced he would not agree to a bill with changes in the park boundary. The measure passed in June; Roosevelt signed it on June 11, 1906. After 42 years as a state park, Yosemite Valley was under federal control again.

CONCLUSION

One political impact of the media publicity given to Yellowstone, Yosemite, and wilderness preservation ideas was that by the turn of the century the nation entered a new era of land management. Among the changes: the Adirondack Forest Preserve was created in 1885; in 1891, the federal government created the first comprehensive Forest Preserve Act; President Harrison set aside 13 million acres in two years of his administration. In 1894, the Lacey Act passed Congress in response to the poaching at Yellowstone. The act provided for a $1,000 fine and up to two years of incarceration — a jail was built in the park — for anyone caught removing mineral deposits, cutting timber or poaching game. President Grover Cleveland closed national forest preserves to unrestricted mining in 1897, to the outrage of Westerners. The Sierra Club played an informal, advisory role in the 1897 passage of the Forest Management Act, which established the federal Division of Forestry, with Gifford Pinchot as its head. Mount Rainier National Park was established under federal auspices in 1899.

The media-savvy Roosevelt and his administration increased national awareness of conservation by solidifying and increasing the federal government’s role in the protection of natural resources, particularly land preservation. During his terms as president, Roosevelt set aside 150 million acres in forest reserves, national parks and national monuments. And land preservation was not the only area in which the young conservation movement was flexing its muscles. Birds, fish and wild game had already been the subject of extensive conservation efforts and a class-based social conflict by the time Roosevelt assumed national prominence (see Chapter One). The social system of the United States became more accepting of the ideas of the conservationists and the nation’s media — with some local exceptions — went along for the ride. The coalition of power groups, the mass media and the environmentalists continued in the case of the Alaskan land affair.

The issue of local versus national control, reflected in the newspapers which represented each interest, did not go away. Similar controversies flared up again in the mid-1990s debate in Washington, D.C., over returning some federal control over natural resources to state and local governments.

REFERENCES

Lafayette H. Bunnell, “The Date of the Discovery of Yosemite,” Century, September 1890: 796.

Alfred Runte, Yosemite: The Embattled Wilderness (Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1990): 11. Tenaya was killed in 1853 in a dispute with the Mono Indians at Mono Lake, where he had fled from the soldiers.

“The Big Trees of California,” Harper’s Weekly, June 5, 1858: 357.

“An Immense Tree,” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, October 1, 1853: 217.

Horace Greeley, An Overland Journey (New York: Knopf, 1964): 267. Originally published in 1860.

Harper’s: 357.

Hans Huth, Yosemite: The Story of An Idea, (Yosemite National Park: Yosemite Natural History Association, 1948): 27.

Donald Worster, Nature’s Economy: The Roots of Ecology (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1977).

James Russell Lowell, “Humanity to Trees,” The Crayon, March 1857: 96.

John Muir, Our National Parks (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1991): 255. Unfortunately for the Navy, Congress declined to provide for penalties until 1831.

The Calaveras Grove, which was split into northern and southern sections, was not protected by the state until 1931 (northern) and 1954 (southern).

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature” in Nature, Addresses and Lectures: The Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson (Boston: Standard Library edition, 1883) Vol. 1: 15-16.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden and other Writings, Brooks Atkinson, ed., (New York: Random House, 1950): 51.

George Perkins Marsh, Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Condition (New York: Scribner & Co., 1869): 35, 228, 235.

Henry Nash Smith, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1950): 168-173. See also Roger W. Finley and Daniel A. Farber, Environmental Law, 2nd ed., (St. Paul: West Publishing, 1988): 335-336.

A.A. Hayes Jr., “Vacation Aspects of Colorado,” Harper’s Monthly, March 1880: 542-57.

John Ise, Our National Park Policy: A Critical History (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press, 1961): 17.

Ise, National Park: 13.

The Country Gentleman, October 8, 1856: 43.

Greeley, Overland: 254.

Mark Twain, Roughing It (New York: Harper, 1913): 161-62.

Greeley, Overland: 259.

Ibid: 262.

Greeley, Overland: 257. John Muir did his first newspaper writing for Greeley’s paper, publishing an article on Yosemite glaciers in the New York Herald Tribune in 1871.

S. 203, 38th Congress, 1st Session, Congressional Record, March 28, 1864: 1310; May 17, 1864: 2300, Stat 13: 325.

Huth, Story: 29-31.

Ise, National Park: 53.

Alfred Runte, National Parks: The American Experience (Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1979).

Stat. 13: 325.

Samuel Bowles, Across the Continent (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1865): 223.

Ibid: 231.

In 1869, more than 1,100 visitors traveled to Yosemite, after the Central Pacific Road reached Stockton. In 1900, after the area was expanded, 5,000 persons visited the park. By the 1990s, the park hosted three million visitors per year.

Leo Marx, “American Institutions and Ecological Ideals,” Science, 170, November 27, 1970: 945-952.

For more on Niagara Falls, see Charles Mason Dow, Anthology and Bibliography of Niagara Falls, Volume II,(Albany, N.Y.: State of New York, 1921), especially chapter 11, “Preservation of the Falls.”

Stewart Udall, The Quiet Crisis and the Next Generation (Salt Lake City: Gibbs-Smith, 1988): 58.

Hans Huth, Nature and the American (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1957): 153.

Alfred Runte, Trains of Discovery: Western Railroads and the National Parks (Flagstaff, Ariz.: Northland Press, 1984): 22.

Alston Chase, Playing God in Yellowstone: The Destruction of America’s First National Park (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1987): 266.

Nathaniel P. Langford, “The Wonders of Yellowstone,” Scribner’s Monthly, Vol. 2, May 1871: 10.

Nathaniel P. Langford, “The Wonders of Yellowstone,” (second part), Scribner’s Monthly, Vol. 2, June 1871: 128.

Langford, May 1871: 7.

Olin D. Wheeler, “Nathaniel Pitt Langford: The Vigilante, the Explorer, the Expounder and First Superintendent of the Yellowstone Park,” Minnesota Historical Society Collections (1915): 661.

Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind, 3rd ed., (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982): 350.

Aubrey L. Haines, The Yellowstone Story, Vol. I (Yellowstone National Park: Yellowstone Library and Museum Association, 1977): 74.

F.V. Hayden., “The Wonders of the West II: More About the Yellowstone,” Scribner’s Monthly, Vol. 3, February 1872: 390.

Ibid: 396.

Runte, Trains: 20-22.

Chase, Playing God: 266.

Nash, Wilderness: 111.

Chase, Playing God: 267.

Scribner’s Monthly, “The Yellowstone National Park,” Vol. 4, May 1872: 120.

Ibid: 121.

Chase, Playing God: 16.

See H. Duane Hampton, How the U.S. Cavalry Saved Our National Parks (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1971).

Linnie Marsh Wolfe, ed., John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1938): 352.

See Samuel Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959).

Robert Underwood Johnson, Remembered Yesterdays (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1923).

Daniel Barr Weber, “John Muir: The Function of Wilderness in an Industrial Society,” unpublished Ph.D dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1964.

Linnie Marsh Wolfe, Son of the Wilderness (New York: Knopf, 1945): 227-28. The Kings River region eventually became the home for Sequoia and General Grant national parks.

Robert Underwood Johnson, “The Care of Yosemite Valley,” Century, January 1890: 474.

Phillip Tichenor, George Donohue, and Clarice Olien, Community Conflict and the Press (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage, 1980).

John Muir, “The Treasures of Yosemite,” Century, August 1890: 484.

Ibid: 488.

Muir, “Treasures:” 487.

John Muir, “Features of the Proposed Yosemite National Park,” Century, September 1890: 667.

Century, “Amateur Management of Yosemite Scenery,” September 1890: 798.

Ibid: 798.

Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed, Challenge of the Big Trees (Three Rivers, Calif.: Sequoia Natural History Association, 1990): 69.

Stephen Fox, John Muir and His Legacy: The American Conservation Movement (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1981): 106-107.

Fox, Muir: 107.

Wolfe, John of the Mountains: 349.

Wolfe, Wilderness: 291.

Wolfe, Wilderness: 302-03.

“Sign This,” San Francisco Examiner, January 20, 1905: 4. Another factor in the Examiner’s opposition may have been the paper’s chief legal counsel, J.J. Lerman, who was also secretary of the board of commissioners of the park. The recession bill would cost him his job.

Wolfe, John of the Mountains: 387.

Johnson, Yesterdays: 291.

Ibid: 127-128.

Wolfe, Wilderness: 304.

Susan R. Schrepfer, “Establishing Administrative ‘Standing’: The Sierra Club and the Forest Service, 1897-1956,” Pacific Historical Review, February 1989: 55-81.