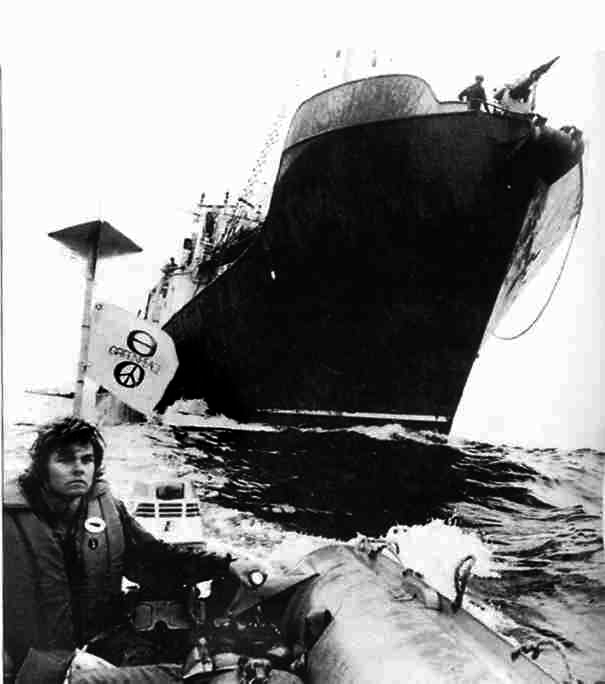

Greenpeace anti-whaling action, late 1970s, Pacific ocean. Photo by Rex Weyler. Used with permission.

by Bill Kovarik

Encyclopedia of Science and Technology Communication, 2009

Marine environmental issues and dramatic protests characterize Greenpeace International, one of the world’s largest and best-known environmental groups.

The organization grew from a small anti-war group formed in 1971 in Vancouver, Canada to an international organization with five ships, 2.8 million supporters, 27 national and regional offices and a presence in 41 nations by the early 21st century.

Among its thousands of dramatic protests, Greenpeace activists have infiltrated nuclear test sites, shielded whales from harpoons, protected fur seals from clubs and blocked ocean-going barges from dumping radioactive waste.

These dramatic tactics were inspired by a confrontational, non-violent philosophy rooted in the Quaker concept of bearing witness and also in the nonviolent interventions of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. The organization’s strict adherence to non-violence has led some groups who long for a more muscular activism to break away from Greenpeace.

The protest tactics were also inspired by an idea that co-founder Robert Hunter called a “mind bomb” – that is, an action that would create a dramatic new impression to replace an old cliché. The classic “mind bomb” involved the use of motorized inflatable lifeboats to shield whales from harpoons, shifting the “Moby Dick” image of heroic whalers to one of heroic ecologists risking their lives to save the gentle giants of the sea.

This approach caught the world’s attention and dramatically changed the political terrain for commercial fishing and whaling operations after Greenpeace’s first whaling protests in June of 1975.

Even before that, Greenpeace organizers first noticed the power of dramatic protest in 1971 when they imagined a new kind of protest amid an intense international controversy over US nuclear weapons testing in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. They chartered a fishing trawler to sail into the test area in the expectation that the US government would have to call off the test. The trawler originally had the name “Greenpeace,” while the group originally called itself the “Don’t Make a Wave” committee, the fear at the time being that nuclear weapons tests could create tidal waves. The trawler Greenpeace sailed from Vancouver on Sept. 15, 1971 but turned back because of weather. When the atomic test was detonated two months later, most of the news articles detailing the protests did not mention the visionary voyage from Vancouver.

Undaunted, a Greenpeace sailboat did managed to sail into the French nuclear testing area of Moruroa in the summer of 1972. When a French warship accidentally collided with the small wooden sailboat, the protest gained news coverage around the world.

The Greenpeace anti-whaling campaign began in 1974 with training on zodiac inflatable boats using outboard motors. The summer campaign in 1975 was launched to confront whaling vessels on the high seas off the US and Canadian Pacific Coast. When a Russian factory whaling ship fired a harpoon perilously close to one zodiac in late June, the incident touched off a media frenzy at a scientific meeting of the International Whaling Commission in London. The fight to save the whales changed that day, said Rex Weyler, a Greenpeace historian.

Along with drama, Greenpeace campaigners continued attacking the idea of a “scientific” group exterminating the last whales and presented evidence that even flimsy rules against taking young whales were being ignored. Meanwhile, similar campaigns were mounted against radioactive waste dumping at sea and against killing seals for fur.

By the early 1980s, the combination of tactics – dramatic confrontations and impassioned arguments – led to bans on sealing by the European Union and a moratorium on most whaling by the International Whaling Commission.

It also led to financial success, and in 1978, Greenpeace was able to buy a 417-ton research ship Sir William Hardy and rename it the Rainbow Warrior, in honor of a Cree Indian prophesy: When the earth became poisoned by humans, a group of people from all nations calling themselves Warriors of the Rainbow would band together to defend nature.

With success in Europe and the US, Greenpeace decided to protest French nuclear testing on Mururoa Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. The Rainbow Warrior was taking on provisions in Aukland, New Zealand on July 10, 1985 when explosions ripped through its hull, killing crewman Fernando Pereira and sinking the ship.

Two agents with the French Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE) were arrested by late July and, by September 22, 1985, the French government conceded that its scuba-diving agents planted magnetic mines and sank the vessel. The French agents were jailed briefly, but released after France threatened to block New Zealand’s exports to the European Union. The French apologized and paid seven million dollars to Greenpeace, but the nuclear tests continued and no one in the French government was held accountable.

Yet the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior underscored the prominence that Greenpeace had attained in the fifteen years since its founding. By the early 1990s it was considered the “green giant” of the environmental movement with protests of every conceivable environmental issue underway in every corner of the globe. Usually the protests involved actions designed to highlight an issue in a dramatic or humorous way, such as dumping marbles in the Dept. of Interior lobby in Washington DC because the Secretary of Interior had “lost his marbles.” Greenpeace also fanned the flames of international outrage in 1995 when the Nigerian government executed environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, who had been leading a nonviolent campaign against environmental destruction of the Niger River Delta caused by Shell Oil Co.

Despite its popularity, Greenpeace was not seen as a “serious” environmental group for many years, and was often excluded from coalitions attacking environmental problems in legal or legislative arenas. One Greenpeace co-founder, Patrick Moore, quit the organization over its stand on chlorine and dioxin in 1986 and started working against Greenpeace and on behalf of nuclear power companies. As a federation of national membership organizations, Greenpeace also has had internal controversy over its budgets and its lines of authority.

However, Greenpeace has had many successes in dramatizing the issues and motivating activists at the grass roots. In the early years of the 21st century, the organization continued its main focus on dramatic action over international marine environmental issues

http://www.greenpeace.org/international/

Michael Brown and John May, The Greenpeace Story. New York, Dorling Kindersley, 1991.

Peter Heller, The Whale Warriors: The Battle at the Bottom of the World to Save the Planet’s Largest Mammals, Free Press, 2007.

Clark Norton, “Green Giant,” Washington Post, Sept. 3, 1989, N24.

Paul Watson, Seal Wars: Twenty-five Years on the Front Lines with the Harp Seals, Firefly Books, 2003.

Rex Weyler, Greenpeace: How a Group of Ecologists, Journalists, and Visionaries Changed the World, Rodale Books, 2004.

William Willoya and Vinson Brown, Warriors of the Rainbow: Strange and Prophetic Dreams of the Indians, Naturegraph Publishers, 1963.