1890 — End of the American Frontier — Superintendent of the Census reports: “Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line.” The significance of the frontier was that it influenced Americans as much as (or some argued, more than) European culture.

“Up to our own day American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West… [The frontier produced] a man of coarseness and strength…acuteness and inquisitiveness, [of] that practical and inventive turn of mind…[full of] restless and nervous energy… that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom…. The paths of the pioneers have widened into broad highways. The forest clearing has expanded into affluent commonwealths. Let us see to it that the ideals of the pioneer in his log cabin shall enlarge into the spiritual life of a democracy where civic power shall dominate and utilize individual achievement for the common good.” — Frederick Jackson Turner.

1890 — General Federation of Women’s Clubs founded in the US; conservation and “ecology” among top priorities. Over a million women participated directly in reform efforts during the Progressive era, and the federation developed national committees on forestry, waterways and rivers and harbors. For example, the waterways committee was formed in 1909 to promote water power, clean water and cheaper transportation, according to historian Carolyn Merchant.

“The rationale for women’s involvement [in public health movements] lay in the effect of waterways on every American home: Pure water meant health; impure meant disease and death.” — Carolyn Merchant.

1890, April 7 — Marjorie Stoneman Douglas is born in Minneapolis, Minn. As a writer for the Miami Herald, she will lead the crusade to save the Florida Everglades beginning in the 1920s. She wrote The Everglades: River of Grass, published in 1947, the same year President Harry F. Truman establishes Everglades National Park. She was also honored by President Bill Clinton in 1993.

1890, Sept. 25 — Sequoia National Park established

Oct. 1 — Yosemite and General Grant National Parks established by an act of Congress.

1891 — Forest Reserve Act passes Congress. Over 17.5 million acres set aside by 1893.

1891 — Baltimore inventor Clarence Kemp patents first commercial Climax Solar Water Heater. By 1910, the Climax had competition, especially from the Night and Day solar hot water company, which used a secondary loop from the collector to a water tank. By 1920, over 5,000 Night and Day heaters had been sold in California At the same time, a boom in solar hot water heaters started in Florida, where electricity was a very expensive competitor. About 15,000 units were sold by 1937. (Butti & Perlin)

1891 — Baltimore inventor Clarence Kemp patents first commercial Climax Solar Water Heater. By 1910, the Climax had competition, especially from the Night and Day solar hot water company, which used a secondary loop from the collector to a water tank. By 1920, over 5,000 Night and Day heaters had been sold in California At the same time, a boom in solar hot water heaters started in Florida, where electricity was a very expensive competitor. About 15,000 units were sold by 1937. (Butti & Perlin)

1891 — Factory Act amendments (UK) Special Rules for medical examination of workers are applied to dangerous industries. The Act was amended many times by recommendation of medical commitees to deal with specific industrial dangers, especially in 1939, 1959 and 1961.

1891, Dec. 31– The Forestry Association opposes new logging permits after pressure from the public to preserve national forestlands. The association hopes to be “arousing public opinion to a full measure of threatened misfortune,” reports the Washington Post.

1892 — Inventor Aubrey Eneas founds Solar Motor Company of Boston to build solar-powered motors to replace steam engines powered by coal or wood (Butti & Perlin)

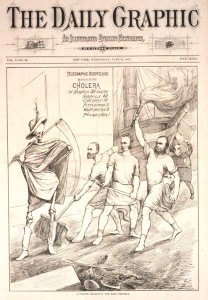

1892 — Europe’s last great cholera outbreak. In one widely noted incident, the disease takes a heavy toll in Hamburg, Germany but spares neighboring Altona. The difference is that Altona has a water purification system.

1892 — May 28 — Sierra Club founded by John Muir, Robert Underwood Johnson and William Colby “to do something for the wilderness and make the mountains glad.”

1892 — 1,000 Londoners die in smog incident.

1893 — Illinois is the first state to pass a law limiting the workday for women to 8 hours. The law is largely the work of Florence Kelly, the first Chief Inspector of Factories for Illinois, who vigorously and tenaciously enforces workday, child labor and sweatshop laws.

1893 –“Shadows from the Walls of Death, or Arsenical Wall-papers” is published in Michigan. Putting arsenic in wallpaper made a vivid green color, but it also was poisonous. The Michigan board of health, as part of its investigation, published a book of wallpaper samples and distributed it to libraries. Unfortunately, the book of samples itself caused poisoning when patrons simply thumbed through their copies. Although laws against dangerous colorants were common in Europe, industries in America claimed that the concept of public health regulation flew in the face of liberty. From the first proposals by public health advocates dating from 1872, states began passing laws limiting the amount of arsenic in wallpaper in 1900. (Shattuck, 1893, quoted in Whorton, 1974).

1894 — Cleaning up New York — A reform-oriented New York City administration appoints Col. George E. Waring Jr. to head the Dept. of Street Cleaning. Before Waring, the corrupt department had not coped with the accumulation of dirt, ashes, garbage, snow and the 2.5 million pounds of manure left by the city’s 60,000 horses every day. Waring’s concern for public health leads to enormous improvements in general sanitation around the city. Heaps of rubbish and manure on every street are swept up by a cleaning force that, itself, is cleaned up. The popular image of a man in the white coat pushing a broom and pulling a round wheeled dustbin is a reflection of Waring’s new approach to street cleaning. Yet if streets were cleaner, other sources of pollution continue to plague New York:

“Waring did nothing to tackle the growing problem of industrial pollution. Hunter’s Point chemical plants continued to pour toxic by-products into Dutch Kills and Newtown Creek. Oil leaks and spills created a constant danger of petroleum vapor conflagration therre, and in Newark Bay as well, but as one Queens newspaper noted: ‘The petroleum industry is of such overwhelming magnitude and importance and is operated by such heavy combinations of capital that it is doubtful whether even by an appeal to the State Legislature’ the oil pollution could be stopped.” (Burrows & Wallace, Gotham, p. 1196).

Horse power also created horse residue, as this 1971 article by Joel Tarr points out:

Sanitary experts in the early part of the twentieth century agreed that the normal city horse produced between fifteen and thirty pounds of manure a day, with the average being something like twenty-two pounds. Ina city like Milwaukee in 1907, for instance, with a human population of 350,000 and a horse population of 12,500, this meant 133 tons of manure a day, for a daily average of nearly three-quarters of a pound of manure for each resident. Or, as health officials in Rochester, New York, calculated in 1900, the fifteen thousand horses in that city produced enough manure in a year to make a pile 175 feet high covering an acre of ground and breeding sixteen billion flies, each one a potential spreader of germs.

1895 — The Illinois State Supreme Court strikes down a law restricting women’s workdays to 8 hours. Two years later, Florence Kelly will be removed from office with the election of a new governor. Similar decisions invalidating workers compensation and labor laws will be made by the courts through the 1930s. (See 1911).

1895 — Oct. 19 — Lewis Mumford born. Historian of technology, influenced by Patrick Geddes, Mumford’s 1934 book Technics and Civilization contends that the industrial revolution was well under way by the late 18th century and would have occurred without any use of fossil fuels such as coal and oil. He argued that the original organic unity between the city and the country had been disrupted by the mining camp culture of fossil fuels use. He saw 19th century Europe as having a “savagely deteriorated environment” but looked forward to a post-industrial phase of culture based on non polluting energy like solar and hyroelectric power.

1895 — The American SPCA and American Humane Association abandon active lobbying to protect wildlife and wildlife habitat, in a still shadowy political division of roles associated with the ASPCA obtaining the New York City pound contract while the AHA obtained the New York state contract to operate orphanages. Legislative efforts to ban hunting–which had nearly succeeded at one point–were dropped, while the lead role on wildlife issues was ceded to the organization which had been the N.Y. State Association for the Preservation of Game, merged with the New York Sportsmen’s Club at some point, and eventually metamorphized through further mergers and alliances into the New York Conservation Council, the original New York affiliate of NWF. Under the ASPCA, the former practice of drowning stray dogs in the Hudson River was replaced by gassing them. The number of homeless animals killed by the ASPCA soared over 100,000 per year in 1908, and averaged more than 250,000 per year from 1966 through 1968, when Lloyd Tait, DVM, started the first ASPCA discount dog and cat sterilization program. The ASPCA killed only 40,000 animals in 1994, then turned animal control duties over to the newly formed Center for Animal Care & Control. Under the CACC, the toll dropped to 35,000 in fiscal 2002. (M. Clifton, 2007)

1895 — Sewage cleanup in London means the return of some fish species (grilse, whitebait, flounder, eel, smelt) to the Thames River. (Fitter).

1895 — US Attorney General Judson harmon tells Mexico that the US will “do whatever it pleases” with water from the Rio Grande.

1895 — American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society is founded.

1896 — George Washington Carver joins Tuskegee Institute, begins research on industrial uses for farm crops. The idea would later expand into the concept of “farm Chemurgy” backed by Henry Ford and others as a way to improve American agriculture and introduce renewable energy systems into general commerce.

1896, April — Swedish chemist Svante August Arrhenius sumarizes scientific opinion about the effect of carbon dioxide (carbonic acid) in the atmosphere, predicting a global temperature increase of 8 or 9 degrees F for a doubling of C02 in the atmosphere. ” On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground.” Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Series 5. 41 (251): 239-276. Available for download at (http://www.globalwarmingart.com/images/1/18/Arrhenius.pdf).

1896 — Public Health in European Capitals written by Thomas Morison Legge (1863-1932).

1896 — Samuel P. Langley writes The New Astronomy (Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p 115) in which he imagines a future in which coal has been depleted and people turn to solar energy: “The rivers are clean again, harbor shows only white sails, and England’s ‘black country’ is green once more.”

1897 — Forest Management Act authorizes commercial use of public forests in the United States.

1897 — Bernard de Voto born — Historian, journalist, and an outspoken conservationist, DeVoto wrote about threats of overgrazing, mining, and lumbering on public lands. He was a columnist for Harper’s and the author of the Pulitzer-Prize winning Across the Wide Missouri. In the mid-1950s he helped mobilize opposition to dam construction in Dinosaur National Monument, in Colorado and Utah.

1897 — December — National Geographic publishes an essay by F.H. Newell, chief hydrographer for the US Geological Survey entitled “Pollution of the Potomac River.”

1898, Oct. 16 — William O. Douglas born. Appointed to the US Supreme court in 1939, retired in 1975, Douglas was a champion of the environment. He was author of A Wilderness Bill of Rights (published in 1965) and an activist for environmental causes while a justice. For example, in 1954, Douglas organized a 189 mile hike along the C & O canal towpath to protest a proposed highway into the park area along the river west of Washington DC. Thanks to his efforts the the highway plans were abandoned. In a 1951 interview with Edward R. Murrow on the program “This I Believe,” Douglas said:

These days I see America identified more and more with material things, less and less with spiritual standards. These days I see America acting abroad as an arrogant, selfish, greedy nation interested only in guns and dollars, not in people and their hopes and aspirations. We need a faith that dedicates us to something bigger and more important than ourselves or our possessions. Only if we have that faith will we able to guide the destiny of nations in this the most critical period of world history

1898 — Steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie tells a Chamber of Commerce meeting in 1898, that smoke was driving people “to leave Pittsburgh and reside under skies less clouded than ours.” Carnegie says: “The man who abolishes the Smoke Nuisance in Pittsburgh… [will earn] our deepest gratitude.” A Committee on Smoke Abatement is appointed by the chamber, but the Engineer’s Society of Allegheny County refused to cooperate. Legislation, not engineering, is needed. By 1906, Pittsburgh establishes ordinances and a smoke inspector’s office. Gross emissions noticeably decreased. The city loses a legal challenge in 1911 when the Pennsylvania Supreme Court says that only the state legislature, and not city governments, has the authority to create smoke abatement laws. Within months, the Pennsylvania legislature specifically gives city governments that authority.

1898 — Coal Smoke Abatement Society formed to pressure government agencies to enforce pollution laws in England.

1899 — March 3 — Rivers and Harbors Act (also called the Refuse Act) passed by Congress. The act is primarily aimed at preservation of navigable waters, but under Section 13 it becomes unlawful to throw garbage and refuse into navigable waters except with a Corps of Engineers permit. One exception is for liquid sewage from streets and sewers. Violators would be fined up to $2,500 and imprisoned up to one year. The new law consolidated four previous laws and had far-reaching implications. Dumping of oil, acids or other chemicals into streams was now prohibited insofar as navigation was obstructed, and in several cases the Supreme Court interpreted obstruction in a broad rather than narrow sense.