Some day soon, an oil & gas industry representative will probably tell a journalist, or a politician, or a concerned parent: “Fracking water is as safe as dish soap. Check out the 2014 University of Colorado study.”

Some day soon, an oil & gas industry representative will probably tell a journalist, or a politician, or a concerned parent: “Fracking water is as safe as dish soap. Check out the 2014 University of Colorado study.”

And of course that will be horribly wrong, but very few people will know why.

This is particularly important in light of New York governor Andrew Cuomo’s announcement that a state health department study found that fracking is too dangerous for New York state (as reported in the NY Times Dec. 17, 2014.)

At best, people will chalk the difference up to the old adage: For every PhD, there is an equal and opposite PhD. But nothing could be further from the truth.

So why would New York ban fracking? Didn’t the University of Colorado just say fracking chemicals are as safe as soap? Things can go pretty far off track when science meets the press, and when we hear or read shallow generalizations based on studies inaccurately interpreted, we wonder how it could have happened.

The 2014 Colorado fracking story is an example of one of many chains of errors in the science reporting system. It started with a scientific paper about a new technique for identifying surfactants (soapy substances) in fracking wastewater. The chain of errors ended with the oil and gas industry’s claim that fracking was a “responsible” practice and the facts on fracking “aren’t so scary at all.”

The chain began in August 27, 2014, with a University of Colorado study about a new method for tracing fracking fluids by using soapy surfactants as an indicator. The study is part of a long-term study about fracking fluids, but this August, 2014 paper focused on a new technique involving one component of the fluids that happened to not be toxic.

Then a November 11, 2014 University of Colorado press release focused on the idea that among the many ingredients in fracking fluids, the kinds of soapy surfactants being widely used are not a problem, according to a new study.

The next day, journalists wrote that fracking fluids were mostly safe.

KUNC, NPR radio affiliate, Denver, Nov. 12 – “Study finds shared chemicals between tooth paste, ice cream, and fracking fluid.“

USA Today, Washington DC, Nov. 12 — “Many common chemicals found in fracking fluid.” At least USA Today had this caveat: The Colorado study didn’t examine all components of fracking fluid, and researchers cautioned that the makeup of the fluid can change from well to well, as drillers use different recipes depending on the underlying rock.

Washington Post, Nov. 12 — “Study: Fracking chemicals found in toothpaste and ice cream.” — A study of one component found in the fracking fluid injected into shale to release oil and gas contains chemicals found in substances most people ingest all the time, including ice cream, laxatives and toothpaste, according to new research from the University of Colorado at Boulder.

KMGH, ABC affiliate, Denver, Nov. 12 — “CU Researchers: Fracking Chemicals studied for first time.” – “The ‘surfactant’ chemicals found in samples of fracking fluid collected in five states were no more toxic than those commonly found in homes, according to a first-of-its-kind analysis by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder.”

Boulder Daily Camera, Boulder, Colorado, Nov 12 — “The chemicals found in fracking fluid collected in five states — including Colorado — were no more toxic than common household substances, according to a newly released study by researchers at the University of Colorado.” The story has since been corrected to read that “Some of the chemicals found in fracking fluid collected in five states…”

From there it was only a short step to the idea that fracking is entirely safe, as in here (in the Daily Camera story): “Anti-fracking activists have been making alarming claims on this subject for many years, but the facts aren’t so scary at all,” said Courtney Loper, the western field director for Energy in Depth. “The chemicals the oil and natural gas industry uses in hydraulic fracturing are a tiny fraction of the total fluid composition, and many are very similar to the kinds of products you keep under your sink and that other industries use routinely without controversy.”

(And here in the ABC story): “We welcome and embrace sound science, thorough studies, and continued transparency. For Colorado families, this should again give comfort that oil and gas development is being conducted responsibly.” This according to Doug Flanders, Director of Policy and External Affairs, Colorado Oil & Gas Association.

This chain of events and stories shows how things can go wrong on several levels.

False analogy: The false analogy that surfactants used by people are safe in the environment. In fact, surface water releases of surfactants can pose problems for aquatic life, and in some cases, toxic surfactants can cause fish kills. And it is these surface water releases that are the problem.

Over-generalization: A highly focused methodological study was generalized into what appeared to be a report giving (or implying) a thumbs up on the overall safety of fracking chemicals. This is a far cry from the intent of the scientists.

Avoiding the real issue: The broad idea that “most” of a waste stream is non-toxic avoids the serious policy question involving the overall toxicity of fracking fluids.

It’s a familiar tactic. The Tennessee Valley Authority used it during the 2008 coal ash disasater, saying that “most” of the chemicals in coal ash waste were so safe they could be used in bowling balls. But the overall mass balance of the toxic release included thousands of pounds of arsenic, thorium, and other heavy metals and poisons which actually made coal ash a serious pollutant. Very few in the press caught the distinction between “harmless” and “mostly harmless.”

Experienced science writers caught the over-generalization problem right away, and made sure that the story referred to only a part of the fracking waste stream. The Washington Post reporter had no problem, but the copy editor who wrote the headline must not have spent much time thinking about it.

Others ended up correcting the story later, after it became a topic of discussion in the Society of Environmental Journalists e-mail discussion list.

The more serious problem this illustrates is one of information process: Scientists finish a portion of their research and look to a university writer for advice on publicizing the work. After consultations, a news “hook” is devised, and a press release is sent out. Local TV, radio and newspapers drop by the university to cover it, and it becomes grist for the daily national news feed because it is topical. Everyone wants to know how toxic fracking chemicals are. And when a story says, ‘not so much,’ everyone rushes to the apparent conclusion because we’re in such a hurry to get to the bottom line.

There is no hint here, that, for all our computer-mediated powers of communication, we have managed to find a way to intelligently organize the public side of the search for scientific truth.

——-

Bill Kovarik, PhD, is a Professor of Environmental Writing at Unity College in Maine.

Ford Quadracycle

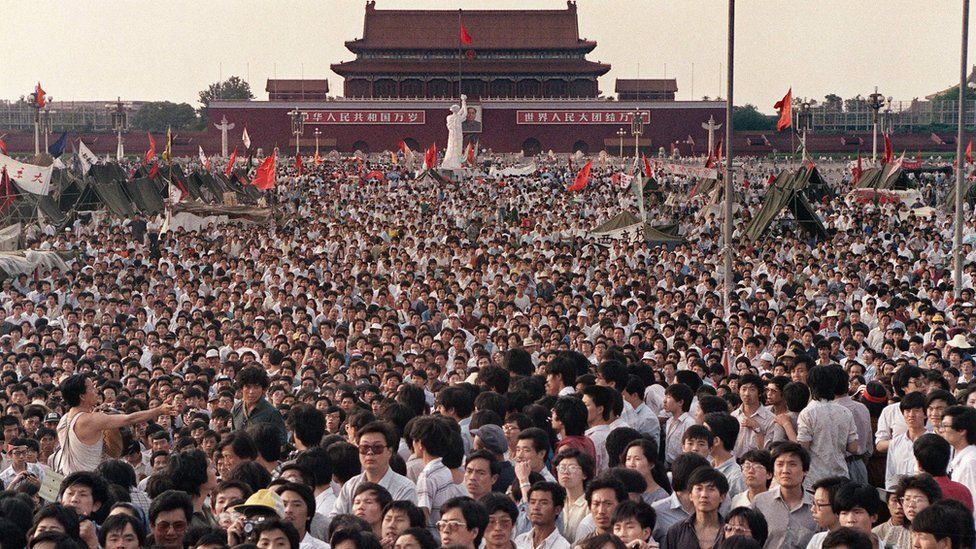

Ford Quadracycle  Tiananmen Square protests crushed

Tiananmen Square protests crushed

Environmental Action Archive

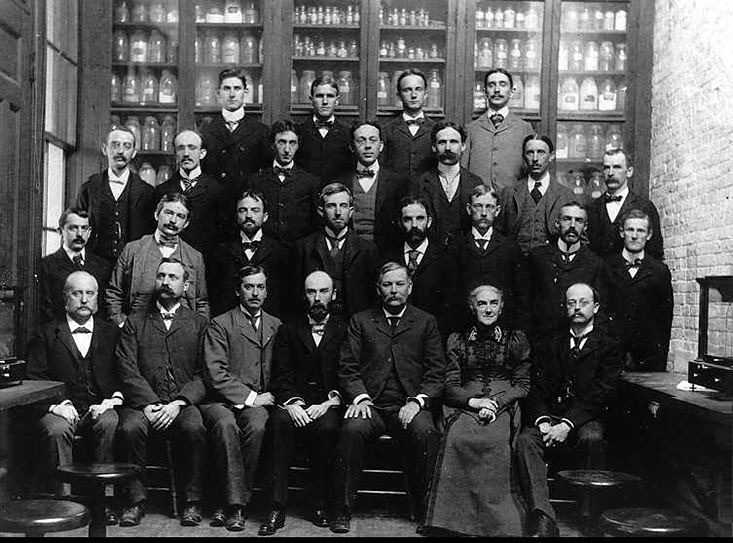

Environmental Action Archive Ellen Swallow Richards

Ellen Swallow Richards The hats that created bird sanctuaries

The hats that created bird sanctuaries  Pollution regs saved lives

Pollution regs saved lives ¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The

¶ A giant tree's death sparked the conservation movement in 1853. Terrific article by Leo Hickman of the Guardian on June 27, 2013. The ¶ Dymaxion car

¶ Dymaxion car  ¶ Aldo Leopold

¶ Aldo Leopold